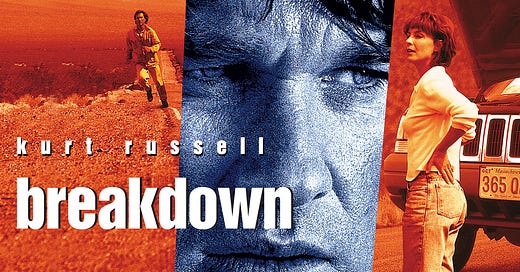

A Life Through Film #052: Breakdown

Kurt Russell stars in a strong entry in the canon of "Guy trying to find their wife" movies

Release Date: 5/2/1997

Weeks at Number One: 1

Thanks for reading! This is my ongoing series where I track the evolution of American culture in my life by reviewing every number one film at the weekend box office since I was born in chronological order. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading my introduction post here, and be sure to like and share the review if you enjoyed it!

Ideally, if you’ve learned anything from reading this column (and I hope you’ve been paying attention, there will be a quiz later), it’s that any movie being made at all is a miracle.

The careful, constant attention that has to be paid to the disparate audio, visual, and narrative elements that interweave to create this thing we call cinema is, frankly, absurd. An unfortunately easy shorthand that we often use when writing about film focuses on a few visible auteurs behind the camera and select major stars in front of it, but movie credits roll ever onward for a reason. The biggest blockbuster and the thriftiest indie would both collapse during production without the right crew working all the jobs most audience members don’t even think about.

And not every movie can be Empire Strikes Back or Twelve Monkeys. No career light board operator or key grip has escaped making some real dogshit. These films too are miracles, albeit ones that no one likes and are often forgotten about. Making one of those must be absolutely miserable, even if you’re getting paid a decent wage to do it. Majorly cursed productions like The Island of Dr. Moreau are one thing, but most stinkers go off without much in the way of technical hitches. On the surface, everything about filming and editing goes fine. An outside observer could see a snapshot of this production and assume that whatever movie is being made will turn out great.

Instead, personal morale plummets as it dawns on everyone on set that all their time and effort has been placed towards a flawed execution of what may have been a good idea at one point. They still have to work, still have to try their best, but everyone’s had a job where they just weren’t feeling it. Every step and motion is dreamlike and sluggish. A small pit sits in your stomach in anticipation of the day being over; it sits next to all those screams you swallowed when a meeting was called to discuss the next fruitless steps towards cascading dead ends. Mediocre lunch becomes breathtaking sanctuary.

In 1996, Jonathan Mostow astutely recognized that his crew were exhibiting these signs. The writer/director finally managed to get the truth out of his First Assistant Director in the final weeks of production: collective faith in the movie they were making was waning. Even with more filming to come and the editing bay waiting, they just couldn’t see Mostow’s vision from their perspective.

If I was Jonathan Mostow in this situation, I would be terrified. He was relatively inexperienced as a filmmaker but had surrounded himself with Hollywood veterans on his first major picture. If the hardworking crewmembers that make the American cinematic engine turn had their doubts, who was he to push back and reaffirm his faith in the project?

The director later admitted to feeling depressed after this exchange, but thankfully that dejection didn’t last long. Months later and with the final edit of his movie in hand, Mostow’s capabilities as a filmmaker were validated. He and the rest of that unsure crew had made a movie they could be proud of, even as it stood apart from almost every other film from its era.

Even nearly 30 years ago in 1997, Breakdown was considered a throwback. By 2025 standards, it’s a miracle. Midsized budget, compelling premise, strong production values, and a bonafide star at its center to carry the whole project along. As the film business began to revolve more and more around major studio tentpoles, Mostow’s tense little thriller set itself apart a relatively small movie that gets under your skin and stays there long after those credits roll. Not through big gimmicks or camp, but through capable filmmaking.

Breakdown was never the biggest hit in the world, so there’s a good chance you have no idea what it’s about. Allow me an elevator pitch: Jeff and Amy Taylor (Kurt Russel and Kathleen Quinlan) are moving from Boston to San Diego when their car breaks down somewhere in the middle of the desolate southwest. A friendly trucker soon passes by and offers Amy a ride to a nearby café, but as more and more time passes without word from his wife, Jeff realizes something suspicious is afoot. Soon, a dangerous kidnapping plot is revealed, forcing this out of depth everyman into a whole new world of peril.

It’s hardly a deep or layered narrative, which makes sense when you discover its origins. After making the low budget (and low quality) indie horror comedy Beverly Hills Bodysnatchers [1/5] in 1989, Jonathan Mostow was struggling to finish his next project, a military thriller called Flight of Black Angel. The money was running out, and the director was struggling to figure out next steps. Serendipitously, a poker buddy at the time was working for long-time Italian film producer Dino de Laurentiis, and connected the two men to get the movie finished (Flight of Black Angel ended up releasing directly to Showtime).

De Laurentiis had been behind movies both major and minor for decades by the time he met Mostow. Actually, that’s being a bit generous. The Italian native mostly worked in the business of shlock, with a filmography dominated by trashy action movies, random foreign imports, and cheap horror flicks. It’s a production strategy that focuses more on quantity of output rather than quality, but occasionally the stars align and you get an actual classic movie out of it. In de Laurentii’s case, it earned him an Oscar early on for Fellini’s La Strada and my heart decades later when he produced Evil Dead II [4/5].

(Also, stereotypes are never okay, no matter which group they center on. I’d just like to point out that during his youth in Italy, Dino de Laurentiis worked at his father’s spaghetti factory alongside his brother, Luigi.)

One small but important deviation in the timeline here. In the early ‘90s, Mostow began developing an idea for a thriller called The Game, which he hoped to write and direct with Kyle MacLachlan in the lead role. It was during this development process that the director met Kurt Russell, hoping to entice him into the project. Though Mostow’s version of The Game was never produced, the process allowed him to develop a connection with one of the most versatile leading men of the 20th century.

Russell came to acting prominence as a frequent child (and eventually young adult) star in many, many oft-forgotten live action Disney productions of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Classics like…The Horse in the Gray Flannel Suit? Or uh, Superdad? See, this is why the Disney Renaissance was so important; without that singular focus on quality animated features, the studio was just making all sorts of stuff that has simply not stood the test of time. Russell, despite the steady, mouse-eared paychecks, knew that his talents were being wasted, and made a hard career pivot at the dawn of the ‘80s.

In 1981, Russell starred in his last Disney project for many years when he voiced Copper in The Fox and the Hound [3/5]. That same year, he redefined scifi action cinema when he teamed up with John Carpenter for Escape from New York [3/5]. Even if you’ve never seen this movie, you’ve felt its impact in the near fifty years since its release. Its grungy, dystopian future aesthetic painted a grim picture of a future dominated by unfettered capitalism. Russell’s antihero protagonist, Snake Plissken, is the no-nonsense inspiration of characters across movies, television, video games, and literature. Even by the time Breakdown came out in ‘97, fictional dystopias in films and games were still looking an awful lot like Escape from New York.

I don’t love Escape from New York as much as some others do1, but it hit theaters like a movie from a decade in the future. Importantly for the context of this column, it solidified Kurt Russell as a real badass grown-up.

Or did it? See, a lot of people define Kurt Russell’s filmography by his copious action work in the ‘80s and ‘90s, stuff like Tango and Cash or Big Trouble in Little China [3.5/5], but he’s an extremely versatile star. All those years of Disney movies had given him plenty of opportunity to practice his comedic chops, why waste that? Russell made just as many spoofs and romcoms in this era of career as he did intense action movies, and they were often just as successful and well-regarded. Action movie buffs often put him in the same iconoclastic category as Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, but Kurt Russell is far more than that one genre.

Mostow recognized this versatility and kept it in his back pocket. Even though his version of The Game never came to pass (more on that in a future column!), he relished the connection he felt with Russell, and vowed to work with him in the future in a way that utilized his unique versatility.

A few years later, Mostow and de Laurentiis decided to collaborate once again, this time on an adaptation of the Stephen King story Trucks. King himself had actually already adapted his work back in the ‘80s in his sole directorial outing, the much maligned Maximum Overdrive. De Laurentiis and Mostow felt enough time had passed to take another shot at it with someone who had actually made movies before at the helm. However, after the director scouted remote desert locations and acquired the necessary semitrucks for filming, licensing for the project fell through, meaning they couldn’t use King’s valuable name in the title of the film. Trucks would never sell tickets without it; they needed a stronger hook.

De Laurentiis put Mostow on the spot. The young director, unwilling to let another project slip away after The Game, pitched an idea off the top of his head: a couple deals with a violent kidnapping plot in the distant reaches of the Southwest, all centered around a truck driver and his criminal cohort. Mostow later said he had been inspired by a friend of his in the FBI remarking how often missing adults slip through the cracks. Maybe he was conscious of the crisscrossing roads and highways of the American desert appearing as symbolic cracks across the landscape, or maybe that’s just an interesting coincidence.

The producer was interested enough in Mostow’s idea to allow him to write a spec script over the course of the next month. The filmmaker fleshed out his idea a bit more, but was conscious of the restraints of independent filmmaking. Mostow was expecting a budget of, at most, $4 million, so his movie had cost-saving measures built into it from the ground up. The American Southwest isn’t just a striking setting visually, it’s filled with remote stretches of road and dusty hillsides where you don’t need to worry about applying for a filming permit.

The main inspiration for Breakdown was a type of film that had fallen out of fashion by the mid 1990s. As he wrote, Mostow remembered the countless thrillers he had seen on television when he was growing up in the ‘70s, filled with normal people going through terrifying ordeals at the hands of menacing strangers. Many of these pictures were made directly for television broadcast, adding to their ephemeral nature in Mostow’s memory. The filmmaker found these concepts so intensely compelling, and though often formulaic, the best of these thrillers could capitalize on the simple terror of never being quite sure how much you could trust your fellow man.

Mostow took his Breakdown script to an approving de Laurentiis, and pre-production began. The director reached back out to Kurt Russell for the lead role of Jeff Taylor, and the actor was immediately intrigued. This role would be unlike any he’d ever played before, as close to a normal human being as he’d ever gotten onscreen. No badass action abilities, no great mind for comedy, no dashing suaveness. Russell would instead be portraying a regular man caught in terrifying circumstances.

Based on this and a friendly connection with Mostow, Russell was almost ready to agree to star in Breakdown, but there was a problem. He and long-time partner Goldie Hawn alternated which of them would be making a movie at a given time so that someone would always be home to keep an eye on their kids, and she was planning to head to set soon for a new project (which, based on the timeline, was either First Wives Club or Woody Allen’s Everyone Says I Love You, both of which came out in ‘96). Russell, then, needed to be home for the kids every night, and couldn’t commit to filming that took place out in the middle of Utah and Arizona.

Desperate to keep their first (and only) choice for the lead, Mostow and de Laurentiis agreed to a frankly ludicrous and absurdly expensive solution. Every morning, a private jet would fly Russell from LA to the remote filming location, and after filming wrapped up at 4:30, it would fly him right back home. That way, the actor was able to sleep at home each night and keep an eye on his kids before leaving the next day. Nowadays, there would be countless op-eds and Substack essays about the localized ecological disaster that this was, but in 1996, it was just cinematic problem solving at its best.

The final version of Breakdown doesn’t feel like a movie that involved multiple daily private jet charters. It’s almost brutally simple, even minimalist at times. The film is economical with its storytelling and relies on the viewer to be able to piece together small contextual clues and moments of visual storytelling in order to get the full scope of its narrative. That’s not to say that it’s a stuffy arthouse flick though; even taking Breakdown just at surface value, its thrills can keep you tied to the edge of your seat with razor wire, while its escalation of scope and conspiracy will have you dramatically off-kilter from scene to scene.

Kurt Russell is in every scene of Breakdown, and at first it is jarring to see the actor playing such a normal guy. An alternative opening that was shot but ultimately cut showed Jeff Taylor’s background as a war photographer, revealing secret survival capability that better explains his actions in the rest of the film. Its removal, however, casts him instead as just a normal guy moving cross country with his wife, forced into action through powerful primal feelings: fear, anger, love, hate, all of which drive him forward to save his love from intensely dangerous circumstances.

Russell’s performance ended up being my favorite part of Breakdown. Surprise surprise, an adeptly versatile actor was able to mix it up once again. As he and Mostow refined the script of the film before shooting (Russell was filming the ill-fated sequel Escape from L.A. at the time), the director was surprised by how willing his star was to cross out line after line of dialogue.

“I don’t need to say this,” Russell explained. “I can just act it instead.”

This self-confidence was not misplaced. All those emotions I mentioned above read clear as day on Russell’s expressive face, as do the plans he silently makes as a result of them. I wouldn’t say the remaining dialogue is filled with gems, but it's tastefully naturalistic in a way that adds to the overall heightened realism of Breakdown. Russell ends up shouting “Tell me where my wife is!” a lot, but that doesn’t tell the whole story of his performance. Every twitch of his wide eyes, every shuddering quiet breath, and every thoughtfully pursed lip tell the story of Jeff’s struggle well enough that monologues to no one (but himself) aren’t necessary.

Mostow wrote Breakdown intending for all of Jeff’s decisions to be the smartest ones he could have made in the moment. That doesn’t always mean the right call, mind you, just that he always does the best he can given the circumstances and what he knows. There’s an occasional disconnect in that strategy when the movie needs a particularly exhilarating stunt scene, but often I felt myself connecting to Taylor as a character both because of this writing and Russell’s performance.

The man gets no backstory, but through his actions you understand his character; what kind of person would duct tape his kidnapper to a car seat by the neck and torture him by slamming on the breaks, all while still wearing their disheveled preppy polo? The movie doesn’t have to come out and say that our protagonist has latent anger issues rooted in anxiety. You just see it.

The (somewhat) realistic events and decisions of Breakdown don’t just enhance the characters, but the thrills as well. Watching a character in another movie running from a big monster or slasher villain is scary prima facie, but the fear really only exists in the context of watching the movie. Once the credits roll, it’s pretty easy to compartmentalize that tension in your body. It’s not real, after all.

Breakdown, though, utilizes threats that feel all too real because they can be. Isolation, paranoia on the open road, and the random cruelty of strangers are all valid fears rooted in the world we live in between trips to the movies. Breakdown doesn’t go too far above realism in depicting these threats until its finale, making it easier to connect to the threats that Jeff and his wife face throughout the film.

And what a primary threat. Character actor JT Walsh plays the central villain of the movie, Red Barr, with that same level of terrifying believability as the rest of the script. When Walsh, who was both Mostow and Russell’s first pick for the character, first met with the director about the script, Mostow was stunned to see the actor had crossed out most of his written dialogue. But that choice ended up amplifying Barr’s menace significantly, since with so little dialogue there’s no opportunity for Jeff to get any emotional leverage on his tormentor. The trucker wants the couple’s money, plain and simple, and he’s willing to speak plainly about the violence he’ll enact if he doesn’t get it.

The scariest thing about Barr is when Walsh flips the switch. The first couple of times we meet the character, he’s nothing more than a friendly, hardworking semitruck driver who’s as amiable as he is cooperative. Later, we see the villain take a break at home with his family, where he’s a loving father and husband with a great laugh and hardly a hint of the darkness he holds inside. It’s a jarring contrast that adds to the paranoia of the film, since when Barr is in friendly civilian mode, Jeff has to be the maniac threatening him in front of others.

I don’t have better language to describe this, but Walsh is able to switch over to those scary eyes that James Gandolfini would pull out as Tony Soprano to indicate that someone was about to get the brakes beaten off them. Unlike that overly emotional antihero, though, Barr’s menace never physically rises above a frightening simmer. Again, it’s through his horrific actions and small context clues in a few later scenes that we understand the true scope of the character’s villainy, not monologues and exposition. Barr isn’t a character to be reasoned with or appealed to. Despite his normal demeanor, he’s a greedy psychopath that you must simply avoid to have any hope of survival.

Quinlan and the rest of the small cast do well with what they’re given, but this is mostly the Russell and Walsh show. The star actually talked Mostow down from adding more characters to the script, like a secondary protagonist envisioned to be played by Morgan Freeman. The limited ensemble does put more pressure on the actors to consistently do well when cameras are rolling, but the results in Breakdown speak for themselves.

I’ve talked a lot about the movie sticking to a more realistic narrative and structure, but I think I need to qualify that with the word “relatively.” In the context of other action thrillers like, say, Ransom, Breakdown does feel more grounded for the most part. But this is still a movie at the end of the day with a need for rising tensions and memorable set pieces. The escalation of the plot’s stakes as the film goes on are fun, but do make certain moments in the climax a bit generic compared to everything that came before it. By this point while watching, I was fully bought in, but this tonal inconsistency may irritate some viewers.

Though Paramount decided to pick Breakdown up for wide distribution halfway through its development, the movie has some of the trappings of low-budget indie filmmaking. There aren’t any CG shots in the film, and the final cut was edited on film, giving the movie a grainy realism that matches the ‘70s aesthetic that Mostow was going for. There are also a lot of fun, dramatic zooms during some of the movie’s more intense scenes, which necessarily break the tension a bit and also remind me of those old school thrillers that inspired it. These choices may not be for everyone, but they enhanced my appreciation of Breakdown as a throwback.

Nothing that Breakdown does is all that new. It’s a straightforward premise with relatively low stakes, a limited cast, and only a couple distinct locations. However, it executes on its fundamental structure brilliantly, with truly great lead performances from Russell and Walsh elevating what could otherwise be a fun but forgettable thriller. This isn’t one of those movies that will change your life, but Breakdown is a particularly fun thrillride because of how much it strips away. It’s like a rickety wooden roller coaster with a great design: part of the excitement comes from the fear of it going off the rails at any moment.

Regular readers of this column will likely have noticed a slow transition happening over the course of these entries. As time goes on, the major movies released are getting bigger and bigger, with studios focusing more on high budget holiday tentpoles over midsized films with smaller chances of mass appeal. This problem will get worse over time as movies lose the ability to make a significant profit in the home media space, but we’re already seeing the effects of increased production costs thanks to skyrocketing actor rates (thanks, Jim Carrey!) and new expensive digital effects. By this point in 1997, the landscape had already shifted so much that I’m not even sure if To Wong Foo would have gotten such a major studio push had it come out even a year and a half later.

That’s why Breakdown is such a breath of fresh air, despite that breath maybe getting caught in your throat due to the tension of the film. It’s reminiscent of everything from Duel to the more cerebral Hitchcock films to low budget shlock from Cannon Films, yet it doesn’t feel even close to being a mishmash of competing influences. Even in the late ‘90s, these kinds of small, focused movies were slowly getting rarer and rarer. They aren’t disappearing for a long time to come, but Mostow and company could see the writing on the wall already.

That streamlined, throwback approach was much appreciated by critics at the time. Breakdown has an 83% on Rotten Tomatoes, the kind of score that could get me out of the house and into a theater if I saw it today. Roger Ebert really dug it, giving it 3 out of 4 stars while complimenting Mostow and Russell for keeping the tension taut throughout (though he did have moral issues with the ending). Meanwhile, Bob McCabe of Empire also loved it, rating it a 4 out of 5 and marveling at the film’s brilliant simplicity:

The great thing about Breakdown is simply that what you see is what you get. Want 90 minutes of edge of the seat tension? You got it. Want an unravelling nightmare that stays with you long after the movie? You got it. Want a decent performance from Kurt Russell, here firmly playing the ordinary man in an extraordinary situation? You even get that.

Detractors of the film, like San Francisco Examiner critic Barbara Shulgasser, disliked the film for failing to properly explain character motivations beyond “He wants his wife back” and “He wants a lot of money.” Speaking from personal experience, my Dad thought the same thing when we watched this movie together. I appreciated that lack of melodramatic backstory in this case, but I do understand that some people want something greater than reality from their movies. I get it, and I disagree.

Breakdown was never the biggest hit in the world, but it made its money at the box office. It debuted at number one ahead of some much more famous competition (more on that below) with a respectable $12 million gate, stuck around for a few months, and eventually left theaters before the end of August. Compared to some of the movies we’ll be covering in this column in the coming weeks, its $50 million domestic gross is hardly much at all. Mostow has always been happy with that figure though, and with a $36 million production budget (all those private planes must have been expensive), Breakdown was a surprise financial success.

I can’t find specific numbers on how the movie did internationally, so I imagine its foreign success was marginal. Instead, it made back even more money on home video, where its audience continued to grow as people discovered this extremely solid little thriller starring Kurt Russell years after it was first released.

Sadly, this would be the last JT Walsh movie released in his lifetime. In 1998, he passed away from a heart attack at the age of 54.

In 2021, Mostow said in an interview that he always thought that “the audience is much smarter than we give them credit for.” Sometimes I wish I were as optimistic, but in this case I think that mentality paid off for him. Breakdown is a killer execution of an admittedly simple premise, bolstered by careful attention to details and a couple of top notch performances. It’s alternatively bombastic and surprisingly subtle. The result is both fun on the surface and intriguing to think about long after you finish watching.

They may not make them like this anymore, but that doesn’t make Breakdown any less potent all these years later.

Rating: 4/5

What Else Was In Theaters?

‘60s spy spoof Austin Powers: International Man of Mystery released the exact same day as Breakdown, peaking at second place behind Mostow’s thriller. The Mike Meyers comedy was only a moderate hit, pulling in $53 million domestically on a $16 million budget. However, word of mouth and extremely strong home video sales ensured that this shagadelic adventure wouldn’t be the character’s last. We’ll be covering Austin Powers down the line.

Fun movie! My wife adores this series and has sat me down to watch all of them, just another reason to love her. International Man of Mystery is a 3.5/5

Next Week: You in the mood for some kooky French scifi? No? Too bad! We’re multipassing our way into The Fifth Element in next week’s edition of the column.

See you then!

-Will

1982’s The Thing is my preferred Carpenter/Russell collab. That’s a 4.5/5 that’s bordering on full marks