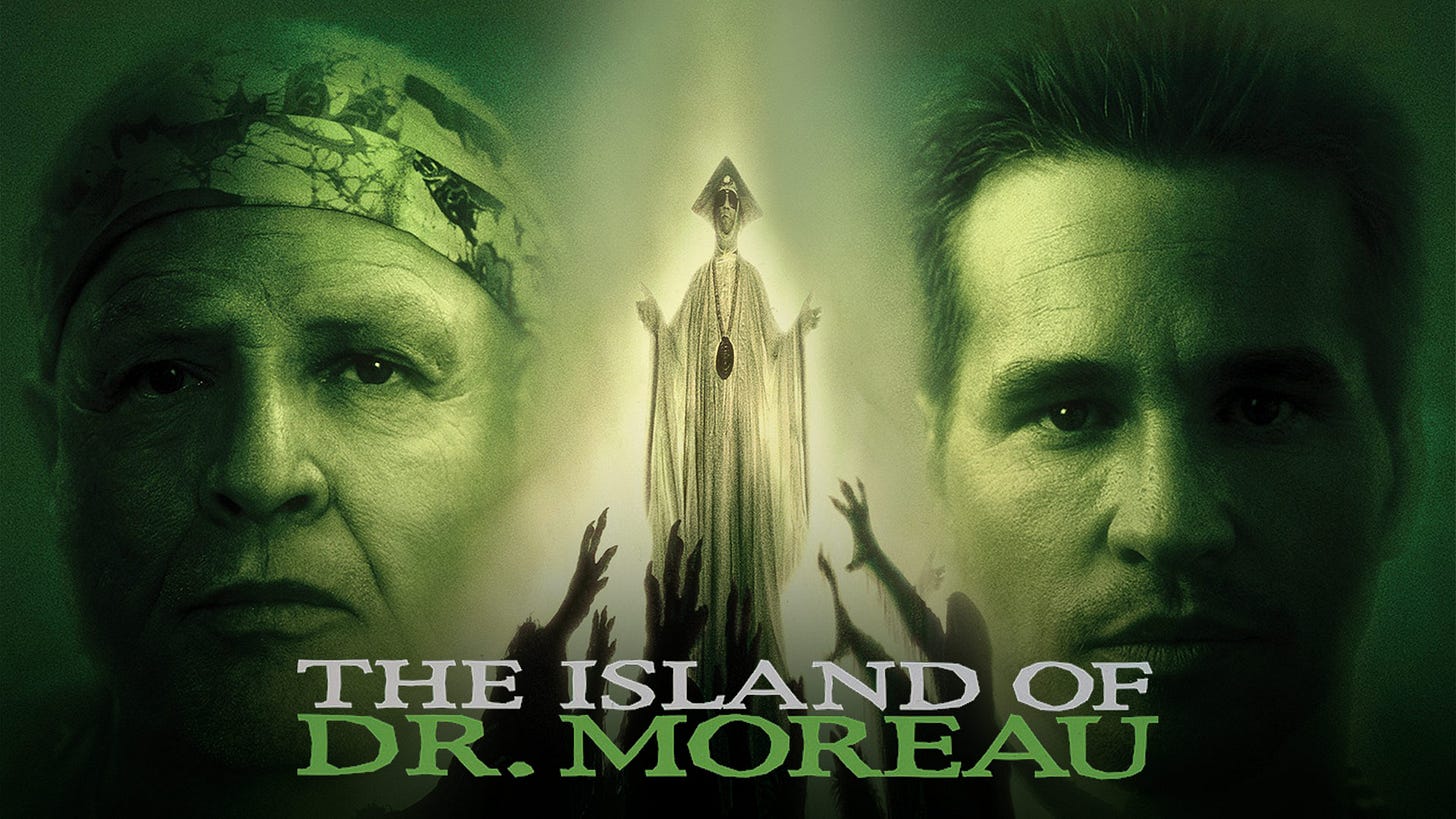

A Life Through Film #030: The Island of Dr. Moreau

We've hit a new low point in terms of movie quality here folks

Release Date: 8/23/1996

Weeks at Number One: 1

Thanks for reading! This is my ongoing series where I track the evolution of American culture in my life by reviewing every number one film at the weekend box office since I was born in chronological order. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading my introduction post here, and be sure to like and share the review if you enjoyed it!

The word “cursed” is maybe one of the more overused pieces of modern internet lexicon. Taking off in 2015, the rise of calling any strange picture or piece of artwork “cursed” as a way to denote its oddness was originally kind of fun, but as internet memes usually go, the fun wore off with time. Overexposure typically doesn’t lead to fondness, after all. But this use of the word isn’t just old, it’s also leading to the kind of reductive language that keeps people from having to fully engage with art.

Things are no longer surreal in a strange, oddly familiar way, they’re “cursed,” similar to how anything that doesn’t set the world on fire is “mid” and any attempt to try to invoke inclusivity is “woke.” After a decade of calling things “cursed,” massive Twitter accounts posting off-kilter photos of people with goofy teeth have effectively sanded down and homogenized strangeness in a way that’s fun to send to the group chat you have with your favorite co-workers.

Maybe I’m overthinking things. After all, I’ve been guilty of similar reductive terminology when I call any movie that gets a little bizarre and sinister “Lynchian.” Who am I to come in and say that people can’t have fun with a silly meme?

I think I’m starting to believe in the original spirit of the word. I’ve tried and tried to think of a better term to describe the production and end result of The Island of Dr. Moreau, but I keep coming back to “cursed.” But how else can you describe it? A warlock’s bones collapsed after he cast a spell so that his director friend would get along with Marlon Brando.

Yeah, I need to just get into this week. No long preamble, just this clusterfuck of a film. The Island of Dr. Moreau is a 1996 sci-fi horror film directed by John Frankenheimer (kind of) starring David Thewlis, Val Kilmer, Fairuza Balk, and Marlon Brando. That’s how I would bill the cast, anyway. The marketing and opening credits place Brando and Kilmer right at the top of the list, to the point where I wasn’t expecting Thewlis to be much of a character at all. Turns out, he’s the protagonist and narrator of the whole film. Christ.

Moreau is based on an 1896 HG Wells novel of the same name, and both film and book follow the same basic premise. A shipwrecked sailor is rescued by a passing ship commandeered by a man named Montgomery and taken to the nearby remote island where he works. There, amid wild jungle, the titular Dr. Moreau lives in exile from polite society as he conducts bizarre experiments to turn animals into something resembling humans. Eventually, his many beast-men rise up against Moreau and Montgomery, leaving the protagonist to try to survive their failing attempt at civilization until he can escape.

Wells’s novel has proven influential over the one hundred plus years since its release. You can find references to the work in music (Devo took the title for their excellent debut album partially from it), other books, television, video games, and movies. In fact, the 1996 adaptation was not even the first swing at a feature-length film version of Moreau. The first, Island of Lost Souls, came out in 1932 and starred Bela Lugosi a year after his legendary turn as Dracula [that Dracula movie holds up, 3.5/5]. 55 years later, another The Island of Dr. Moreau starred Burt Lancaster for a final result that Rotten Tomatoes summarizes as “reasonably entertaining.”

That ‘77 adaptation was a bomb, and though I can’t find financial data for Island of Lost Souls, it wasn’t received well at the time and has achieved only limited cult acclaim in the near century since it was released. So despite the long cultural tail of the novel, its full potential on the big screen remained untapped by the 1990s. But Jurassic Park [3.5/5] had proven that audiences were extremely down to watch an effects-heavy movie about mad science gone wrong on a tropical island. So when a young, English indie director by the name of Richard Stanley began calling around the studios with a script and concept art for a dream adaptation of Moreau in 1994, New Line took him up on it and flew him from London to LA.

The following two years would prove so chaotic for Stanley, New Line, and everyone else caught in the vortex of Dr. Moreau that it was necessary to make an entire separate film to figure out what even happened.

This is the third time I’ve written about a movie in this series that had a separate feature length documentary detailing its production history, but this is a different kind of beast. Full Tilt Boogie [2.5/5] was mostly a video diary of how fun it was to make From Dusk Till Dawn with occasional anti-Union propaganda thrown in as a treat. The Hamster Factor [3/5] compiled onset footage requested by a slightly-paranoid Terry Gilliam and showed the nuts and bolts of Twelve Monkeys being made, with standard levels of dysfunction behind the camera. Budget concerns, creative disagreements between studio and director, poor test audience screenings, stuff like that.

That’s not what we’re dealing with today. Those documentaries were made basically concurrently with their subject film as an extended behind the scenes peak for fans. They don’t really make much sense without the context of close familiarity with From Dusk Till Dawn or Twelve Monkeys, but those movies are well-liked, so their documentaries have a built in audience. The Island of Dr. Moreau doesn’t have that; Lost Soul is an autopsy made nearly two decades after its subject’s release that doesn’t celebrate success so much as examine the crater that still remained after its complete failure. It is for everyone to marvel at in horror.

Disasters almost never start as disasters. New Line were clearly eager to elevate a young filmmaker from the world of micro-budget genre flicks to the mainstream, another trend of the ‘90s they hoped to ride. Stanley was to be the next Tarantino, a hip auteur with a clear creative vision and the tenacity to achieve it. His goal with Moreau was to use the existing story to examine mankind’s evolving relationship with civilization and God, heady subjects to broach in something with rapidly mainstream aspirations.

Early on, the executives at New Line somehow got the script in front of the legendary Marlon Brando. The actor wasn’t exactly at the hottest moment of his career by the mid-1990s; after a legendary ‘70s (The Godfather [5/5], Apocalypse Now, Superman, the controversial Last Tango In Paris), Brando claimed retirement in 1980 but returned by the end of the decade to mostly negative results. A small role in 1992’s Christopher Columbus: The Discovery netted him a Razzie nomination for Worst Supporting Actor, and New Line was already wary of him because of how difficult he had been on the set of their 1995 comedy Don Juan Demarco.

Still, Brando was a name that drew people in, even if he wasn’t a major star. If he was interested, the studio had to capitulate to his wishes. And Brando’s wishes included not wanting to work with an unknown like Richard Stanley. To avoid losing his dream job to Roman Polanski, the director requested a single meeting with Brando to try and change his mind. The studio set up that meeting, but Stanley knew he had to work some magic to get one of the greatest living actors on his side.

That wasn’t a cute turn of phrase I just used. Stanley literally called a warlock buddy of his back in England and asked him to help out. While the director met with Stanley in Los Angeles, this literal pagan magician performed a strange ritual a world away to ensure a fortuitous result. The more superstitious of you are probably panicking at this, but hopefully even the more rational among you can recognize that this is weird behavior. If it’s not opening the door to paranatural, it’s at least opening the door to some uncomfortable conversations with the producers and HR.

I don’t think Brando taking a strong liking to Stanley at that meeting is proof that the warlock’s ritual worked. I do think, however, that the ensuing production of Dr. Moreau is proof that it certainly had some sort of effect on the physical world.

The pre-production and filming of this movie was disastrous on almost every level. Just before Brando was to come to set, his daughter Cheyenne sadly took her own life, sending the actor into a spiral that left his involvement in the film up in the air. Val Kilmer, at the peak of his popularity, joined the cast as Montgomery and was so openly hostile to Stanley and the crew that it almost seemed like intentional sabotage. The remote Australian rainforest they filmed in was buffeted by a hurricane that shut down production for days as soon as they tried to start shooting. Meanwhile, Stanley’s warlock friend had to go to the emergency room because poor protection at his day job as a radiologist made his bones extremely brittle, and while he was there he caught a flesh eating bacteria. I could go on, truly.

New Line heard about repeated conflicts between Kilmer and Stanley (as well all the other nastiness around set) and took the actor’s side, firing Stanley two weeks into filming. The director took this super well. He disappeared into the rainforest to hide and smoke heinous amounts of weed before eventually sneaking his way back onto set in disguise to take part as an extra weeks later.

In the meantime, American director John Frankenheimer was summoned to remote Australia on a week’s notice to replace Stanley. Frankenheimer was an old-school director with a reputation for wrangling difficult actors. And while he was able to get Kilmer under control, this also meant that everyone else bore the brunt of his scream-heavy style of directing, especially poor Fairuza Balk (last seen in this column as one of the best parts of The Craft.)1

And all of that was before Brando finally showed up to set. Once he found his way to Australia, the actor’s presence made shooting somehow even more difficult. Brando kept coming up with wacky ideas for his character that the crew had to abide by, including costume changes that took hours and new props that had to be built for the little person sidekick Moreau just had to have. Don’t worry, he also hated Val Kilmer and the director, ruining production in front of the camera as well.

It’s tempting to give the actor grace considering he was still reeling from the loss of his daughter, but I don’t know if he would have been a much more stable presence had she not sadly died. By this point in his career, Brando was fully disillusioned with acting and the games of Hollywood. This clip from a 1989 interview between him and Connie Chung has gone semi-viral in the past couple of years, and you can tell he just doesn't care about the world of moviemaking or his place in it anymore. And that was years before he came to the already dysfunctional set of Dr. Moreau and made things worse for everyone.

I could go on, but I have to actually talk about the movie at some point. As of writing, both Dr. Moreau and Lost Soul [3/5] are both available for free on Prime Video, and they make for a fascinating double feature. The documentary paints a picture of a production that would make it impossible for the kind of creative collaboration necessary for a good movie to come out of it. I wish I could say that the cast and crew overcame their differences and made a really special piece of sci-fi horror, but I can’t. The Island of Dr. Moreau is garbage.

Kilmer and Brando were such disruptive presences behind the scenes they ended up not having enough time to actually act in the movie they were top-billed in. You can see the disdain that Kilmer has for the whole project with every part of his performance. He delivers lines listlessly with these long pauses between them, almost like he couldn’t believe the words coming out of his mouth. There are a few moments where the physical charisma he exhibited in breakout hits like Top Gun [3/5] shines through once the island devolves into chaos, but his presence more often emits bored anger. When he’s finally put out of his misery towards the finale, it’s a relief as a viewer.

Brando is terrible in an entirely different way. Despite only having 30 minutes of screentime in Dr. Moreau, the title character leaves the strongest impression in the movie because of both the bizarre nature of his scenes and how obviously phoned in the actor’s performance is. His costumes are garish, he covers his body in white body paint because he decided that Moreau hates the sun, and he has the world’s smallest man as a sidekick (in matching outfits!). Brando had infinite ideas for changes that should be made to the movie, but he didn’t care enough to actually read the script and learn his lines.

Instead, an assistant in his trailer read his lines to him through an earpiece, which the actor would then repeat on-camera. And you can tell every word that comes out of Brando’s mouth was just fed to him. He stammers through sentences without any pretense that his character has come up with these lines organically on the spot. The effect is reminiscent of a kindergartner suffering stage fright at the Christmas play and repeating the lines verbatim from his patient teacher in the front row. Between his terrible performance and bizarre appearance, Brando comes off as a sad old clown, not a brilliant actor in the twilight of his storied career.

American actor Rob Morrow was originally supposed to play the protagonist/narrator, but unable to handle the nightmare that was the set, he quit after 4 days. David Thewlis (who you might know as Remus Lupin from the Harry Potter movies) was called in to replace him on short notice. He tries his best, but Thewlis’s performance would need to be Oscar-worthy to counteract the suckage around him. And as decent as he is in Moreau, the Academy was not going to nominate him for all of his running around and confused panting.

Poor Fairuza Balk, man. I had never been aware of her as an actress before watching The Craft, but she was such a compelling presence in that movie. Like everyone else in this cast (except maybe for the extremely vain Val Kilmer), the young Balk was excited by the prospect of working with Brando, especially since she’d be acting as his character’s daughter. But after Stanley left, Balk found herself trapped in The Island of Dr. Moreau2, and Brando couldn’t even talk to her about their characters’ dynamic because he refused to read the script. As a result of all this, her performance lacks all of the edge and allure that her character is clearly meant to have. Her misery leaps off the screen.

Even if Brando had been intimately familiar with the script, I’m not sure if it would have helped. Dr. Moreau plays with big ideas of Man running up against his Creator, but it’s too eager to have compelling themes and forgets to tell a good story first and foremost. Major plot points, like the attempts by the beast-men to emulate humanity, are either never fully explained or glossed over entirely. There’s a big twist at the tail end of this movie that baffles not because of its narrative implications, but because it doesn’t make any goddamn sense. The movie then fails to address it at all afterwards, and I feel stupid for even caring.

The Island of Dr. Moreau is similar to its source material in its themes of Man himself being capable of a backslide into animalistic violence and savagery. I was actually onboard with that until the movie literally spends its final moments monologuing that idea at the viewer complete with a montage of news footage of people getting into fistfights. Not only is this choice heavy-handed, it’s disconnected from the movie we’ve just watched. There are plenty of examples of humanity’s cruelty in the text of Dr. Moreau; if the movie really needed to do a montage, they could have just shown some footage of Montgomery or Moreau and their transgressions against the beast-men. Maybe they didn’t because that would have meant reminding the audience of the two worst performances in the film.

It takes Marlon Brando 30 minutes to show up as Dr. Moreau and his character kicks the bucket a half hour later. The movie wasn’t much of a narrative masterpiece before his stint in it, but the actor’s abysmal performance makes the central ideas around his character impossible to take seriously. This is a role that cries for a nuanced take, both Man and Creator rolled into one figure. But Brando doesn’t give enough of a shit to find the meat in Moreau. He isn’t a cackling villain, nor a troubled antihero. How are we supposed to take the analog for God seriously in this movie when he most resembles a bored art teacher who’s trying his best to get fired? By the time the beast-men reject him and take over the island, it’s almost a blessing that he’s gone.

I recognize that this is a subjective point, but this is just a gross movie to me. Easily, the best aspect about this production was the cool practical effects of Stan Winston, the god of cool practical effects. He and his team designed and built a whole world of animal-man hybrids and created prosthetic suits custom to each actor that took hours every day to put on and take off. These kinds of prosthetics take ages to make, and having them done for so many different actors couldn’t have been cheap, so Dr. Moreau puts them front and center to get their money’s worth.

The problem with that is these designs emphasize the body horror of each beast-man’s transformation. They are intentionally tough to look at, and having them be so present in each shot makes me cringe at times. I’m not saying they’re scary; I wasn’t frightened once during this whole movie despite it technically being a horror film. Instead, I found characters like the pig people and the evil (?) Hyena to be tiresome to look at, despite the craft that went into their construction3. Maybe I’m being unfair, but it’s annoying when the one great element is swallowed up by so much crap. Winston’s work is impressive, but it unfortunately is used to prop up a movie that I find pretty awful.

Dr. Moreau is complex in its bullshit. A lot of money was spent on this film, only for the disparate elements of its production to fight against one another. Dozens of extras in custom beast-men suits of staggering quality underwent months of body language training before filming only to be upstaged by the dual awfulness of Kilmer and Brando’s performances. Thewlis and Balk do alright work, but are let down by an awful final cut that confuses their characters and makes them less compelling in every way. The remote location where they filmed and suffered in isolation was all so that the highest mountain in Queensland would loom in the background of the whole film, but the timing of the shoot meant that there were only 90 minutes in the entirety of the filming process where the peak wasn’t covered by fog and clouds.

I don’t say this a lot, but I hated this movie. I resent having watched it and really don’t care to keep writing about it. Its flaws are numerous and frustrating, but I don’t even have the benefit of being the first to bring the story of its troubled production together. Instead, I’ve just shown up years too late to add anything new to a conversation that’s been ongoing for decades. The Island of Dr. Moreau is a terrible movie. It’s not even so goofy as to be fun to watch like Street Fighter: The Movie [a 1.5/5 in execution, but a 5/5 in my heart].

More often than not, Moreau is just frustratingly boring. It’s too self-important despite having nothing to offer but half-baked ideas lifted straight from its century-old source material and some admittedly solid costuming. This was not an island I enjoyed visiting, and I will not be returning anytime soon.

Critics at the time also disliked the movie, but honestly I think they could have torn into it even more. A 23% on Rotten Tomatoes means almost 1 in 4 reviewers recommended the film, which may warrant an investigation into a possible payola scheme. Thankfully, you can also find plenty of reviewers baffled by Brando and annoyed by the script. I like this line from Peter Stack in his review of Dr. Moreau for SF Gate:

The filmmakers insist that every moment is a moral flash point. But the whole thing collapses under the weight of its hokum.

The Razzie Awards are made for studio suckage like this. The film received 6 nominations at the anti-Oscars, including Kilmer and Brando both being up for Worst Supporting Actor. The only win was for Brando however, with the film itself losing Worst Picture to the Demi Moore led cinematic disaster Striptease.4

Regular readers of this series know that just because a movie tops the Box Office for a weekend, that doesn’t make it a financial success. The Island of Dr. Moreau was able to win a very slow weekend by pulling in $9 million over those first three days, probably off the back of Brando and Kilmer being top billed. Once everyone realized how awful the film was though, people stopped showing up, and it rapidly slid down the charts. It barely stayed in theaters for two months, and only ended up making $27 million domestically on a $40 million budget. Wikipedia says it made another $20 million internationally, but I can’t find a source for that. Either way, this shit flopped.

The legacy of Dr. Moreau is ruin. Richard Stanley finally emerged from the jungles of Australia only to flee to the French countryside, where he only made sporadic indie films for decades. Don’t feel too bad for him though; he got a chance at redemption with the much-hyped HP Lovecraft adaptation Color Out of Space in 2019, but after abuse allegations came out against him I doubt he’ll be working much again after that movie underperformed.

Meanwhile, Brando never worked in anything so prominent again, his legendary career capped off in the minds of many with an equally legendary flop. Kilmer kept acting and was a success for a few more years, but a reputation of being too difficult to work with, built on stories from sets like Moreau’s, eventually caught up with him. He’ll appear a few more times in this column, but don’t expect his presence to extend much past the new millennium.

Everyone involved with The Island of Dr. Moreau learned a lesson from the disaster of its creation. Marlon Brando learned that he was truly done with acting after years of resenting it. Richard Stanley learned to never work with Val Kilmer or big studios ever again. New Line learned that not everyone can make Jurassic Park. These are all valuable takeaways from this movie, but as an outside observer, I think there’s one major thing to keep in mind from Dr. Moreau if you ever find yourself at the helm for a new motion picture.

No matter how much you want an actor to like you, do not get a warlock involved.

Rating: 1/5

Next Week: What do you do if your lead actor dies while making a movie but you release it anyway and it becomes a surprise hit? Of course, you make a sequel that does its best to copy the first movie! It’s time to watch The Crow: City of Angels.

See you then!

-Will

Balk had been close with Stanley and threatened to walk once he was fired. Her management assured her she’d never work in Hollywood again if she did, so she spent the rest of production as a hostage to her own career being screamed at by a director who didn’t understand what he was doing there. Jesus.

Curious that Rob Morrow was able to exit the movie despite playing a more major role and went on to have a solid career in television. Curious!

Don’t worry, the movie also has some of the worst CG I’ve seen yet in this column. There’s a scene with some inexplicable rat-men that made me cradle my head in my hands in cringe