A Life Through Film #047: The Star Wars Special Editions

For decades, George Lucas was disappointed by his greatest creations. Now, it was time to make things right.

Release Date: 1/31/1997

Weeks at Number One: 6

Thanks for reading! This is my ongoing series where I track the evolution of American culture in my life by reviewing every number one film at the weekend box office since I was born in chronological order. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading my introduction post here, and be sure to like and share the review if you enjoyed it!

When I was a kid, my family was fully bought in on this new company called Netflix that would send us DVDs in the mail. As the barriers preventing us from watching any movie we wanted at any time began to fall, my siblings and I finally had an easy way to fill the major gaps in our cinematic backlogs.1 On special occasions of watching big movies that the whole family could enjoy, my parents would sometimes organize Nacho Movie Nights.

The premise was simple: a nacho bar in the kitchen with homemade fixings, a great movie in the DVD player, courtesy of Netflix. A rare opportunity to eat dinner and watch the TV at the same time, all while encoding the value of the shared cinematic experience with those you love.

I don’t remember many specific movies that we watched for Nacho Movie Night, but I can never forget the overwhelming feeling of positivity I get just thinking about the ritual. I was probably already fond of both its central elements by the time we started combining them, but to this day I still consider nachos my favorite food and watching movies with others one of my favorite activities.

Something else that’s lingered on as a favorite? The franchise I associate most with Nacho Movie Night.

I don’t think there’s a better first way to experience Star Wars than as a child munching down on delicious junk food. The bright colors and flashing lights, the incredible costumes and spaceships, and the classic narrative of good versus evil all appealed directly to the pleasure centers of my young mind. And it isn’t like it was all new to me on this first watch. By this point in the 2000s, I had gleaned much of the franchise via cultural osmosis, and seen far more impressive technical feats in more recent movies. Yet Star Wars still drips with that special sauce that, if it catches you at the right moment, can linger with you forever.

Obviously, I’m nowhere near the only person who’s ever had that feeling.

The original Star Wars trilogy, released between 1977 and 1983, invented the Hollywood blockbuster as we know it today. Its staggering financial success was unprecedented, as was the strategy that director George Lucas used to achieve it. Star Wars (as the first movie was simply known back then) overtook The Godfather [5/5] to become the highest grossing movie of all time, but it didn’t do it by offering a superior sterling example of storytelling. Instead, it used bright lights, simple characters, and cool imagery to draw in a wide audience of both children and adults. You’ll recognize this as the root description of every major motion picture that comes out these days.

Lucas, by his own admission, cares more about kinetic motion and visuals than characters and narrative dialogue. He cast aside the rich, layered plots employed by friends like Brian de Palma, Steven Spielberg, and Martin Scorsese to make a movie filled with the things he loved.

The resulting trilogy lacks irony, pretension, and many other trappings of Lucas’s peers. In an era of post-modern filmmaking, Star Wars was an earnest morality play filled with space magic and cool dogfights. It remains one of the most critically acclaimed and commercially successful runs of movies ever made.

Lucas, in his decision to forgo his initial director’s fee to retain the merchandising rights, eventually became a billionaire as a result. Star Wars and its two initial sequels won scores of awards, kickstarted entire careers, and allowed their creator to become one of the most important figures in 20th century Hollywood. Their immediate and long-term importance simply cannot be overstated.

As it currently stands, you cannot watch those movies.

George Lucas always felt hampered while making Star Wars. His original draft of the script was so expansive and complex that he eventually split it in two. The first three movies in the franchise is him adapting the second half of that narrative: Luke Skywalker realizing his potential as a Jedi Knight as he helps the Rebel Alliance defeat Darth Vader and the evil Galactic Empire.

Even though he was able to use a groundbreaking combination of models, matte paintings, early computer graphics, and physical sets, Lucas wanted more. As early as 1977, just after the release of the first Star Wars, the director was already telling friends that he’d inevitably go back and fix what he saw as a rough technical execution.

Twenty years later, George Lucas got his wish. He hadn’t directed a film since his first Star Wars feature, acting as a creative guide for its subsequent sequels but preferring instead to move behind the scenes in Hollywood. As the founder and CEO of Industrial Light & Magic, the preeminent visual effects house of the late 20th century, Lucas knew better than anyone the evolving capabilities of computer graphics. ILM has appeared in this column a few times so far for its prominent work on movies like Jumanji and Twister, but it was their work on one movie specifically that moved its big boss to action.

Lucas’s long-time friend and collaborator Steven Spielberg was already untouchable as a filmmaker by 1993, but that year cemented him as a real candidate for the best director to ever live. Critically, he released Schindler’s List, one of the most acclaimed American films of all time, a terrifying, heart-breaking reflection of the Holocaust that won basically every award ever conceived of. On a lighter note, Spielberg also shipped Jurassic Park to multiplexes everywhere that year, a commercial juggernaut that answered the question of “Can we make fake dinosaurs that look good yet?” with a resounding “Fuck yeah we can.”

There’s something special about the way the T-Rex in Jurassic Park [3.5/5] looks that still boggles the mind. Logically, you know you’re watching a special effect in a movie. And yet there are certain shots of this terrifying predator standing in the dark rain where you can’t help but wonder if Steven Spielberg somehow found access to a time machine. Decades later, there still aren’t many computerized attempts at depicting organic life that look better than what ILM was able to conjure up in ‘93.

George Lucas monitored the post-production process of Jurassic Park with great interest. He realized that the movie represented a crossing of the technical Rubicon. Here, at last, was the ability to realistically depict the impossible using digital effects. As Lucas’s employees revolutionized the capabilities of computer graphics, the Hollywood mogul realized that it was time for him to flex his writer/director muscles once again.

Remember when I said that Lucas’s original Star Wars script had been split up into two parts? He was tired of sitting on the first half of that story, the tale of Anakin Skywalker’s falling to the Dark Side and ending the age of the Old Republic. In a moment of hubris that perhaps puts him closer to the Dark Side than not, George Lucas decided that technology had caught up to the creative vision he had had two decades prior. In November of 1994, he began writing the Star Wars Prequel Trilogy.

But as Lucas worked, he had to confront a difficult question. Would people even turn up for a new set of Star Wars movies?

Since the release of Return of the Jedi in 1983, the franchise’s popularity had been a rollercoaster of diminishing pop culture prevalence. The late ‘80s have been referred to as “the Dark Times” by some fans due to a lack of prominent releases in across all mediums. The 10th anniversary of the series was most notably marked by the launch of the Star Tours ride at Disneyland and the release of an official Star Wars tabletop RPG2, indicating that the franchise was already moving into legacy status so soon after it had appeared to change the landscape of film.

It wasn’t until 1991 that public interest in Star Wars began to rise again like a Force ghost, thanks to Lucas’s behind the scenes corporate moves coming to fruition. Heir to the Empire by Timothy Zahn, the first novel in a trilogy that would serve as canonical sequels to the films, was a surprise New York Times Bestseller, as were dozens of subsequent Star Wars novels by both Zahn and other authors. Ironically enough for a franchise so focused on visuals, these books were beloved by fans young and old for their emphasis on fleshing out the lore and timeline of the series.

Meanwhile, LucasArts, the director’s official game studio and publisher, finally began making acclaimed, highly successful Star Wars titles after years of building their reputation with beloved point-and-click adventure games like Maniac Mansion. By 1995, they were one of the biggest game studios in the world, thanks in large part to games like Super Star Wars and Star Wars: TIE Fighter. A merchandising boom followed these successes, with Star Wars toys climbing to such popularity that the only brand on Earth that could surpass it was Barbie.3 Though these toy sales were impressive, the most important piece of Star Wars merchandise remained the movies themselves.

The rise of home video was an enormous boon to the franchise. Long-time fans no longer needed to wait for theatrical rereleases to partake in the galactic adventure again. Even better, VHS copies of A New Hope (as the first movie was now subtitled), The Empire Strikes Back, and Return of the Jedi could now be watched and rewound obsessively by a whole new generation of kids who hadn’t even been alive for the original releases. A potent market had emerged: older fans of the franchise looking to tap into their own nostalgia combined with the first generation of Star Wars enthusiasts to never sit in a theater and watch their favorite movies.

It was proof to Lucas that there would always be fans of what Star Wars had been. Now, he needed to show them what it was about to become.

George, and thus ILM beneath him, had taken the public position that computers were the future. He was writing the Prequels not with practical sets and matte paintings in mind, but entire worlds and even characters crafted with post-production CG.

Lucas was thrilled by the prospect of having full control over the motion and action of his new films, a lack of which was a frustration early in his career due to an inability to fully communicate what he wanted. Mark Hamill has famously speculated that if he could, Lucas would do away with actors entirely. Harrison Ford, the most successful alum of the entire Star Wars franchise not named George, once claimed that the director only ever had two notes for him on-set: “Do it better” and “Slower.”

Lucas went to 20th Century Fox with a plan: give him the money to go back and fix the Original Trilogy’s rougher edges before a wide rerelease, all in promotion of the upcoming Prequels. Fox had been the only studio willing to take a bet on the director back in ‘75, and their faith had paid off handsomely in the decades since. The suits were more than happy to foot the bill for Lucas’s quest to digitally alter the Original Trilogy, which as a whole only cost them about $15 million.

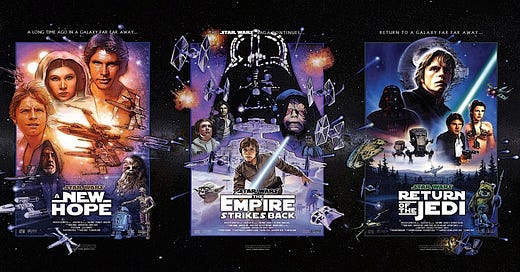

These new versions of the Original Trilogy would be known as the Special Editions, and were marketed to emphasize brilliant new special effects and the first new cinematic Star Wars content in 20 years. Just after Lucas finished writing his Prequels at the tail end of ‘96, the new version of the franchise’s first film released to great fanfare.

On January 31, 1997, Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope (Special Edition) hit 2000 theater screens across the country.

The fan backlash to Lucas’s tampering of his own work is such old news at this point that it’s actually ancient history. Even before I had actually seen Star Wars, I had seen countless bitter, angry posts online about the digital changes made to the original films ahead of the CG bloat of the prequels. This disappointment became a fandom signifier, as ubiquitous to those who love Star Wars as plastic lightsabers.

George Lucas, the target of this ire before the fandom turned on women and minorities later in the 2010s, has wisely stayed mostly offline since 2000. Ironically, he’s happy enough to let his work speak for itself now that he’s done updating it.

As someone who has never been allowed to legally watch the original versions of these Star Wars movies, I don’t feel as strongly about the minor storytelling changes made in the Special Editions as fans who have been worshipping Han Solo since before the Reagan Administration. But it’s undeniable that Lucas adding 1997-era CGI to his original trilogy has aged them far worse in the long run than any questionable blue screen compositing of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s.

We should be fair. The majority of the Special Edition changes are extremely superficial to the point that most will slip right by you, and at the end of the day, these are mostly the same great movies that they have always been.

But every once in a while, just when you got comfortable with your silly space wizard adventure, your childlike wonder is broken by visuals on par with the fucked up monkeys from Jumanji.

The sum result is akin to refrosting a delicious cake and sprinkling a box of Hot Tamales on it as a final garnish. The final product is still delightful, but it looks questionable and occasionally ruins what would otherwise be a perfect bite.

So what did Lucas actually change in the Special Edition rereleases? Let’s start with New Hope.

If it’s been a while, or you’re one of those proud weirdos who brag about having never seen a Star Wars movie, a quick recap. A New Hope is pretty prototypical hero’s journey stuff. Ambitious farmboy Luke Skywalker is thrust into a galactic adventure when droids C-3PO and R2D2 arrive crash land on his planet with the secret plans for the Empire’s Deathstar base. After Imperial Stormtroopers kill his aunt and uncle, Luke joins the droids, old Jedi mentor Obi Wan Kenobi, scoundrel smuggler Han Solo, and giant furry alien Chewbacca on a quest to save the captive Princess Leia, get the Deathstar plans to the Rebel Alliance, and destroy the Empire’s planet-annihilating weapon.

Most of the CG incursion here and in the rest of the Special Editions is cleaned up compositing and enhanced spaceship modeling. As much guff as Lucas gets for doing the Special Editions at all, these specifically are great uses of his new tech. Like I said in my Independence Day and Star Trek: First Contact reviews, as generally poor as computer graphics were at this time at rendering people or animals, they were already quite good for modeling spaceships. Shiny, metallic, and inorganic? Maybe the computer was simply better at self-portraiture at this point in its artistic career.

A few new shots were added to A New Hope that focused on the motion of newly CGI ships like the Millennium Falcon and the Rebel Alliance’s X-Wing armada before the climactic attack on the Death Star. These still look quite good, adding a tangibility to the scifi tech that the carried-over shots of physical models can sometimes lack. I know that sounds counterintuitive, but though impressive feats of physical handiwork, the props built back the ‘70s lack grit and realistic shininess that these spacecraft would have as real vehicles.

If I’m being honest, there are only a few moments when watching A New Hope where the updated visual effects are noticeable, and I’d say half of those are the spaceship changes. The other half? Legitimately, yikes.

Before I knew almost anything else about Star Wars, I knew the phrase “Han shot first.” It’s a bit passé now, but the slogan was at one time a universal shorthand rejection of the changes Lucas made to the Special Editions by highlighting the most egregious example, the rare instance of a new effect having a direct impact on characterization.

George had grown dissatisfied with Han Solo’s character in the decades since the release of A New Hope. His arc in the whole trilogy shifts him from a slimy mercenary to an honest to God galactic hero thanks to the power of love and friendship.

And yet, one of the first things you see Han do is shoot and kill Greedo, a bounty hunter who comes to collect, before the alien can fire a single blast. To fans, this made Han Solo a badass, a true blue rogue whose eventual evolution into a beloved family man feels even more dramatic as a result. To Lucas, Han murdering Greedo invalidated his whole arc. How could Princess Leia marry a cold blooded killer?

In the Special Edition of A New Hope, as Greedo sits across from Han in the seedy Mos Eisley Cantina, he gets a shot off, missing Solo and justifying his own blaster shot as self defense.

The way people online talked about this moment you would have thought that George Lucas had changed the scene so that Han Solo gave Greedo a tender kiss on the lips and sent him on his merry way a changed man. Instead, one of our main characters is made slightly less problematic ahead of his multifilm redemption arc. Even if he shoots second, Han Solo is still extremely cool, and his arc carries narrative heft even if he’s not gunning down rivals in galactic backwaters like Mos Eisley. I’m more personally offended by the shifty digital editing of Harrison Ford’s head to make it look like he dodged the shot before firing back.

I understand this moment as an easy representation of fan disputes with Lucas’s vision, especially in the wake of the Prequels, but “Han Shot First” is too specific and sloganeering to capture my main issue with the Special Editions. I guess “George Lucas filled the screen with bad CGI and made his otherwise beautiful movie hard to look at in certain parts” doesn’t roll off the tongue quite as easily.

Luke and company’s trek through Mos Eisley Spaceport in the moments before Greedo’s demise just looks so bad, man. Lucas inexplicably directed ILM to fill this one setting with all manner of poorly rendered CG extras and sets, all lit so brightly that it’s impossible to ignore their low quality. It’s such a visually horrendous scene that it distracts from the iconic “These aren’t the droids you’re looking for” moment between Obi Wan and some hapless Stormtroopers.

Then, just after Han commits a little justified manslaughter, we get the big new scene in the movie.

Jabba the Hutt, slug-like gangster, didn’t originally appear in this series until Return of the Jedi, but Lucas wanted to test ILM’s capabilities. Using old cut footage that was intended to use stop motion animation in 1977, the SFX wizards at the studio put together…this.

Not only does this look terrible in hindsight, but it slows the movie’s pace to a crawl. Much of the dialogue is recycled from Han’s conversation with Greedo, and none of what he and Jabba talk about makes any sense until near the end of the next movie. Don’t worry, real Star Wars fans: we edited in footage of Boba Fett silently staring at the camera so you can hoot and holler like a bunch of chimpanzees at the cool character that shouldn’t be here yet!

These worst alterations of A New Hope all exist in a very localized space, making about ten minutes of this otherwise incredible scifi adventure film jarring to watch. Maybe I should be a little thankful. Only the scenes set in Mos Eisley are so visually obnoxious, so once the Millennium Falcon takes off from the spaceport, we get the rest of an excellent movie unimpeded.

This first Star Wars entry is a simple morality tale of good underdogs versus evil overlords with inconsistent worldbuilding and so-so acting from everyone involved, and yet it remains greater than the sum of its parts.

The fluctuating tension of the second act aboard the Death Star remains palpable no matter how many times I watch, and the climactic battle against the space station? Lucas somehow transferred his fascination with World War II fighter pilots into the vacuum of space in a way that felt not only natural, but franchise defining. Unlike even its most immediate follow ups, A New Hope contains nothing but earnest excitement for its own world and action. Maybe you think that’s corny, and I can’t really argue against it. But as far as straightforward adventure movies, the first Star Wars remains one of the greatest ever put to film.

Cinematic legacies don’t start out much stronger than this. Despite all this time and George Lucas’s meddling, A New Hope is still a blast. Generally speaking, the Special Edition edits to the film don’t affect much of the movie past a brief window at the end of the first act, but they do allow for a Ship of Theseus-esque thought experiment.

The original Star Wars was a juggernaut at the 50th Academy Awards, where it picked up the Oscars for Film Editing, Visual Effects, Sound, and more. The official version of the movie has been altered so dramatically that it no longer contains the visual effects, audio design, or editing that netted it all those statuettes. Does it still deserve those awards?

Is it even the same movie?

A New Hope was written and directed solely by Lucas, but he stepped away from such responsibilities for its sequels. The Empire Strikes Back, originally released in 1980, credits him with the story, but the screenplay comes from Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan, while the film was directed by Lucas’s USC Film School professor Irvin Kershner. Brackett was primarily a scifi novelist by trade, and though she only turned in a single draft of the sequel’s script before her death in 1978, she is still credited alongside Kasdan, who was about to work with Lucas and Spielberg on Raiders of the Lost Ark [4.5/5].

This motley crew of creatives was a far cry from the singular vision of one auteur, indicating that maybe this sequel would lack the focus of its predecessor. Instead, Star Wars Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back remains the consensus pick for the best movie in the franchise’s history.

So many elements that have gone on to define Star Wars as a brand have their roots with Empire. Emperor Palpatine, the overarching villain of the entire franchise, first appears here, as does the legendary Imperial March theme.4 On the opposite side of the moral spectrum, Yoda, everyone’s favorite little green guy, isn’t mentioned once in A New Hope but is catapulted to major status within the canon thanks entirely to Empire Strikes Back. The love story between Han and Leia, the emotional heart of the Original Trilogy, basically plays out in full over this one movie’s runtime, and I’m barely scratching the surface.

Boba Fett! The Imperial Walkers! Lando Calrissian! That pop-culture altering revelation of parenthood from Darth Vader!

Empire fleshes out the world of Star Wars in such obvious and important ways that it makes you think these elements were there all along. In the same way, the main narrative grows to include more complicated thematic ideas than the black and white morality of the first film.

Luke’s temptation towards the easy power of the Dark Side ends with him facing Darth Vader before he’s ready and losing his hand, pushing him deeper into his moral struggle. Meanwhile, Han and Leia fall in love as they both realize that fighting the Empire is more than just noble space battles and epic victories. Sometimes, fighting a war means choosing the least evil of two options, like when Lando betrays them in order to save his people.

Lucas created Star Wars to fill the morality gap left by the absence of cowboy films, but his Empire collaborators stepping away from that relative moral simplicity left the series with its greatest emotional resonance. The franchise would try with future films, but it never got more romantic than the five words between Leia (“I love you”) and Han (“I know”) before the latter is frozen in carbonite.

Maybe Lucas knew that he really oughta not touch Empire. The Special Edition of the sequel skates by with hardly any noticeable digital changes. Besides cleaner compositing during the Battle for Hoth, the biggest changes happen in the third act when the characters find themselves in the Cloud City of Bespin. In an effort to make the little-seen mining colony feel more fleshed out, Lucas added new external shots using computer graphics, as well as new windows with views of CG skylines. There’s a single five second shot of a ship flying through Cloud City that looks a bit too 1997, but that’s it.

Empire Strikes Back remains the best Star Wars movie for many reasons, and its relatively uniform appearance from 1980 to now is one of them. Lucas picked the cream of the Original Trilogy’s crop to focus on more subtle cosmetic differences, rather than major visual overhauls.

Fittingly, he chose the movie that was already closest to being a toy commercial to go really buckwild with his computers.

Return of the Jedi is the first Star Wars movie where I can kind of get it if you hate it. I disagree, but I get it. By the time of its original release in 1983, the franchise was already more valuable to Lucas as a toy and merchandising line than as a series of movies. As a result, the finale of the Original Trilogy is chock full of new characters, locations, and designs for existing favorites, all available this Christmas in action figure and playset form. It even marks the first instance of the nascent series going back and playing the hits. What’s the big threat this time around? Let’s just do the Death Star again.

Written by Lucas and Kasdan and directed by Richard Marquand, Star Wars Episode VI: Return of the Jedi does also attempt to tie up the trilogy’s overarching threads in between advertising the new Ewok plushies.

After a frankly wacky opening stretch where Luke, Leia, Lando, Chewbacca, and the droids take down Jabba the Hut to save Han, the movie adopts a slightly more serious tone as our heroes face the final wrinkles of their respective arcs. Luke comes face to face with Emperor Palpatine, his last temptation towards the Dark Side. Han and Leia, far from their origins as a gruff smuggler and a prissy princess respectively, lead a final ground assault against the Empire with the underdog assistance of the local Ewok tribes. Lando, seeking redemption for his betrayal in Empire, takes the most dangerous task of the ultimate assault on the last Death Star.

Other narrative ends are less well rounded. George Lucas has said that, as a whole, Star Wars is about redemption, with Darth Vader’s face turn before he dies being the obvious core of that. I think with the later context of the Prequels, Anakin/Vader’s final redemption makes more sense, but in the isolated context of just the Original Trilogy, it doesn’t feel particularly earned. Speaking of rugpulls, the reveal that Luke and Leia were twins all along is an obvious contrivance used to avoid having to explain away a love triangle involving the two and Han more complexly. Just ignore all the kisses and longing looks beforehand, space fans!

Believe it or not, I still love Return of the Jedi. It’s far more fun than the bleak Empire, filled at times with a childlike sense of adventure more reminiscent of A New Hope. The action of the series has evolved to an impressive degree by this point, with the extended lightsaber battle between Luke and Darth Vader being one of my favorites in the whole franchise.

Speaking of Luke, this is probably Mark Hamill’s best performance of the character in the whole Original Trilogy. He fills Skywalker with smarmy confidence all the way up until he’s brought before the Emperor aboard the second Death Star, his Jedi powers now no help at all to his seemingly doomed friends on the planet below. That anger comes out in that lightsaber duel, and makes Luke’s final rejection of the Dark Side even more powerful. Good stuff, Mark!

And I like the Ewoks. I know that as a grown man I’m supposed to find the Ewoks annoying and their inclusion hamfisted, but sorry, I think they’re really cute. Not only that, they’re thematically appropriate. The whole Original Trilogy is the story of guerilla fighters scraping together small victories over the overwhelming force of the Empire. What better way to put the finishing blow to the great systemic threat of the trilogy than to use the rock and stick technology of a tribe of walking teddy bears?

Like A New Hope, most of the major Special Edition edits to Return of the Jedi can be found in one specific section of the movie. The opening mini-adventure to Jabba the Hutt’s palace is filled to bursting with questionable 1997 CG, including my least favorite moment in the entire trilogy. Worried about the danger that our heroes find themselves in in this gangster’s palace? Don’t worry, we’ll get rid of that tension for you. You see, Lucas saw fit to add a pop number to his grand space opera, complete with gibberish lyrics and the ugliest goddamn aliens the series has ever seen.

How was “Jedi Rocks” (yes that’s the name of the song) not the fandom codeword for being mad at George Lucas? It’s a moment as bad as any garbage from the Prequels, and yet all anyone ever wanted to get mad at was Han shooting first. On top of that, the later Jabba scenes that take place in the deserts of Tatooine look especially bad due to the bright sunshine lighting up poor rendering and compositing. The opening twenty minutes of Jedi were already controversial among fans for reasons ranging from pacing issues to Leia’s metal slave bikini, but the egregious new effects give it a real case for being the worst part of these first movies.

Of all the Special Edition changes made to the Original Trilogy, these Jabba related ones are most frustrating to me. I understand why Lucas focused ILM’s computers on these scenes. They’re the least essential to the actual plot of the movie, so if these changes look bad, at least they’re not affecting actually important moments. Plus, the first of the upcoming Prequels would take place largely on Tatooine, so it was important for the studio to get their rendering reps in on the planet now.

But these changes are visible right from the start of the movie. As good as the rest of Jedi is, viewers get a bad taste in their mouth right away, coloring their opinion of the overall film.

The most famous change to Jedi actually wouldn’t occur for another decade after the Special Editions first released. On top of adding new CG shots of other planets celebrating the demise of the Galactic Empire, we get alterations to a more personal moment of the finale as well. Originally, Anakin Skywalker’s silent Force Ghost at the end was played by Sebastian Shaw, the same actor who played the unmasked Darth Vader in his final scene. Nowadays, this role is played by a smug, staring Hayden Christensen, edited in for post-Prequel home media releases to ensure continuity.

I get why this was done, but personally I would have asked for a warmer take from Christensen. Lighten up man!

There was a time when I considered Return of the Jedi to be my favorite Star Wars movie, since it was a fitting conclusion to an excellent trilogy. But while I still think it’s the most fun film in the series to this point, its few narrative foibles and Special Edition butchering keep it from topping my personal tier list. I still really love it though, and it’s always a toss up between it and A New Hope when it comes to second place in the Original Trilogy.

In the long term, fans were not into the Special Edition changes to the OT. It would be one thing if it were still easy to go back and watch the UnSpecial (?) versions of these movies, but from 1997 onward, all official releases of the Original Trilogy on home video and streaming platforms have used the Special Editions. Lucas made his original movies damn near lost media, and though there are ways to watch the same films that audiences saw between 1977 and 1983, they’re inconvenient compared to the official alternative.

So what we’re left with are mostly excellent movies that will always have these echoes of their creator’s dissatisfaction. When you see moments like Greedo shooting first or the many CG details now found in Jabba’s palace, it’s tough to know that these ugly changes were made out of Lucas’s own disappointment with his own work. The major Special Edition changes are scars from where the father of Star Wars tried his own corrective surgery, ones we fans have to live with any time we’re feeling nostalgic.

That nostalgia drove the insane financial success of these rereleases. 20th Century Fox estimated that the trilogy could make $100 million collectively, which would have been a great return on their investment. Instead, A New Hope cleared that figure on its own, pulling in $138 million and topping the box office for three straight weeks. Empire then came out and topped the charts for two weeks, while Jedi finally completed the set with a single week atop the box office.

These staggered releases of the Special Editions allowed fans to get their fill of each movie before the next one came out, and let every individual entry get their moment to shine. With the exception of one weekend where next week’s movie reigned supreme, the original Star Wars trilogy of films dominated the US box office for six weeks at the start of 1997, pulling in a total of $252 million.

An international release was almost just as strong, leading to a final gross of $455 million. Adjusted for inflation, these upgraded rereleases pulled in nearly a billion dollars worldwide.

How did these old movies hold such economic sway two decades after their first release? The new effects may have been a small draw, but the real answer is nostalgia and excitement. Original fans could relive the thrill of the trilogy’s original release, while new fans could see the films on the big screen for the first time. There was also value in looking forward. By this point, the Prequels had already been announced, meaning that fans could use these Special Editions not just as a way to get back in the spirit of the franchise, but to see what the new movies might look like with modern effects.

As divisive as they remain, the Special Edition rereleases of the Original Trilogy smashed expectations and delivered on their ultimate goal. The first three Star Wars movies were no longer just movies; they were marketing tools and technological test beds. Once the Prequels were written, the franchise’s first three movies could no longer just stand on their own. They would be in conversation with the new trilogy, precursors that recontextualized everything audiences had lived with for decades. In a way, fans would now get the experience of being George Lucas.

Lucas had viewed his magnum opus as incomplete since he first split that script in half in 1975. As generations of fans found love and hope in his creation, he stewed and waited for the day when he could tell the rest of his story. In 1997, those same fans could now look at those same movies and be reminded that there was more to the story that remained untold. Two years later, the first chapter of that expanded story dropped and changed perception of Star Wars and George Lucas forever.

One day, we’ll return to the galaxy far far away.

Ratings:

A New Hope: 4.5/5

Empire Strikes Back: 5/5

Return of the Jedi: 4.5/5

What Else Was In Theaters?

Dante’s Peak, a star studded volcano disaster epic, released during A New Hope’s run atop the charts. Believe it or not, we’ll be getting into it more in a few weeks. 3/5

Next Week: So what cultural force was strong enough to unseat Star Wars in 1997? Why, Howard Stern of course! The shock jock gets cinematic in Private Parts.

See you then!

-Will

Actually, I think my older brother was already torrenting like three movies a night at this point, but he still used early Netflix alongside us

If anyone has a rulebook and is down to show me the ropes, please reach out ASAP

A not-insignificant portion of this market was comprised of adult speculators buying new toys in the hopes of an incredible resale value down the line. This wasn’t based on nothing, since some merchandise from the Original Trilogy’s initial release had skyrocketed in value in the ensuing decades, but it’s funny how many adults in the ‘90s were obsessed with holding onto pieces of adolescent ephemera as investments. Beanie Babies are the obvious example, but it was also happening with comic books and, of course, Star Wars figures. Silly, sure, but any more cringe than buying speculative meme coins in hopes of going “to da moon”?

There’s so much I have to talk about here that I haven’t really had a chance to talk about John Williams’s iconic score for the franchise. It’s medium-defining, what else do you want me to say?