A Life Through Film #037: Romeo + Juliet

I never actually had to study this play in school. First time for everything.

Release Date: 11/1/1996

Weeks at Number One: 1

Thanks for reading! This is my ongoing series where I track the evolution of American culture in my life by reviewing every number one film at the weekend box office since I was born in chronological order. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading my introduction post here, and be sure to like and share the review if you enjoyed it!

A couple of months ago, a friend asked me about my research on the movies of the mid ‘90s and wanted to know about trends. Specifically, he wanted to know if I matched his thoughts that the period was the craziest time for movies ever.

I disagree with that take, but I also see his logic. This stretch of time is filled with many trends that feel entirely alien to modern sensibilities, some of which we’ve covered in this column and some of which have passed us by on the periphery. Surely we didn’t need all those erotic thrillers, many of which starred Michael Douglas? A wave of music video directors made the jump to helming feature films (to mixed results), marking the tangible influence of MTV over a decade after its launch. There’s plenty more, some of which I wrote about a few weeks ago in my recap of covering the big movies from the first 12 months of my life.

One trend I haven’t yet encountered is particularly strange. For some reason, the 1990s was absolutely full of Shakespeare.

The Bard’s work is timeless, obviously. High schoolers have been studying the written word of his sonnets and plays for generations, but to quote the great band Turnstile, you really gotta see it live to get it. I’ve seen performances that represent both Shakespeare’s comedies (like As You Like It) and his tragedies (such as King Lear). Those experiences of seeing the man’s centuries-old stories acted out by world-class actors will linger in my mind for a long time.

There have been movie adaptations of Shakespeare’s plays for about as long as there have been movies, but the 1990s in particular saw a big jump in major films finding either direct or indirect inspiration from his work. The most high profile, The Lion King [4/5], is a loose adaptation of Hamlet, but other movies were more outright in their depictions, such as a live-action adaptation of the play in 1990 that starred Mel Gibson. In 1995, there were adaptations of both Othello and Richard III starring Laurence Fishburne and Ian McKellan respectively, and 1996 saw a version of Twelfth Night starring Helena Bonham Carter.

The king and instigator of this whole wave was Kenneth Branagh. As both director and star, the Englishman seemed wholly dedicated to making highly visible adaptations of Shakespeare’s biggest works. His 1989 version of Henry V was a critical darling that kicked this whole trend off, and only a few years later saw Branagh’s adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing in 1993. None of these direct adaptations, including Branagh’s, were massive commercial hits, but they reviewed extremely well and were often in the conversation during awards season.

I found a Reddit post from a few years back that was curious about this phenomenon, and I like the point that its creator makes about the shifting of demographics. According to the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Bard of Avon’s many plays didn’t become regular parts of high school English curriculums until the 1920s or so. Those public education standards became more widely adopted as the years went on, just in time for the Baby Boomers, the largest generation in American history to that point, to reach 9th grade English class.

This led to a generational understanding of William Shakespeare as a prestigious, challenging, and yet unquestionably defining titan of the English language. Once the Boomers reached both positions of power within Hollywood and held a large generational pool of disposable income, high-quality depictions of his stories proved a decently safe commercial prospect. Even if something like Othello didn’t set the box office on fire in 1995, it and dramas like it had a rapt, wealthy audience of high-brow middle-aged viewers, always ready to catch a matinee or rent it later at Blockbuster.

A safe if unambitious model for success. The Lion King, however, proved that there was big money to be made from twisting the Bard’s work around, particularly with stylistic changes that appealed to younger demographics. By 1996, the winds had changed. The Baby Boomers had been carrying the torch of Shakespeare’s work for years now.

It was time for Gen X to take over.

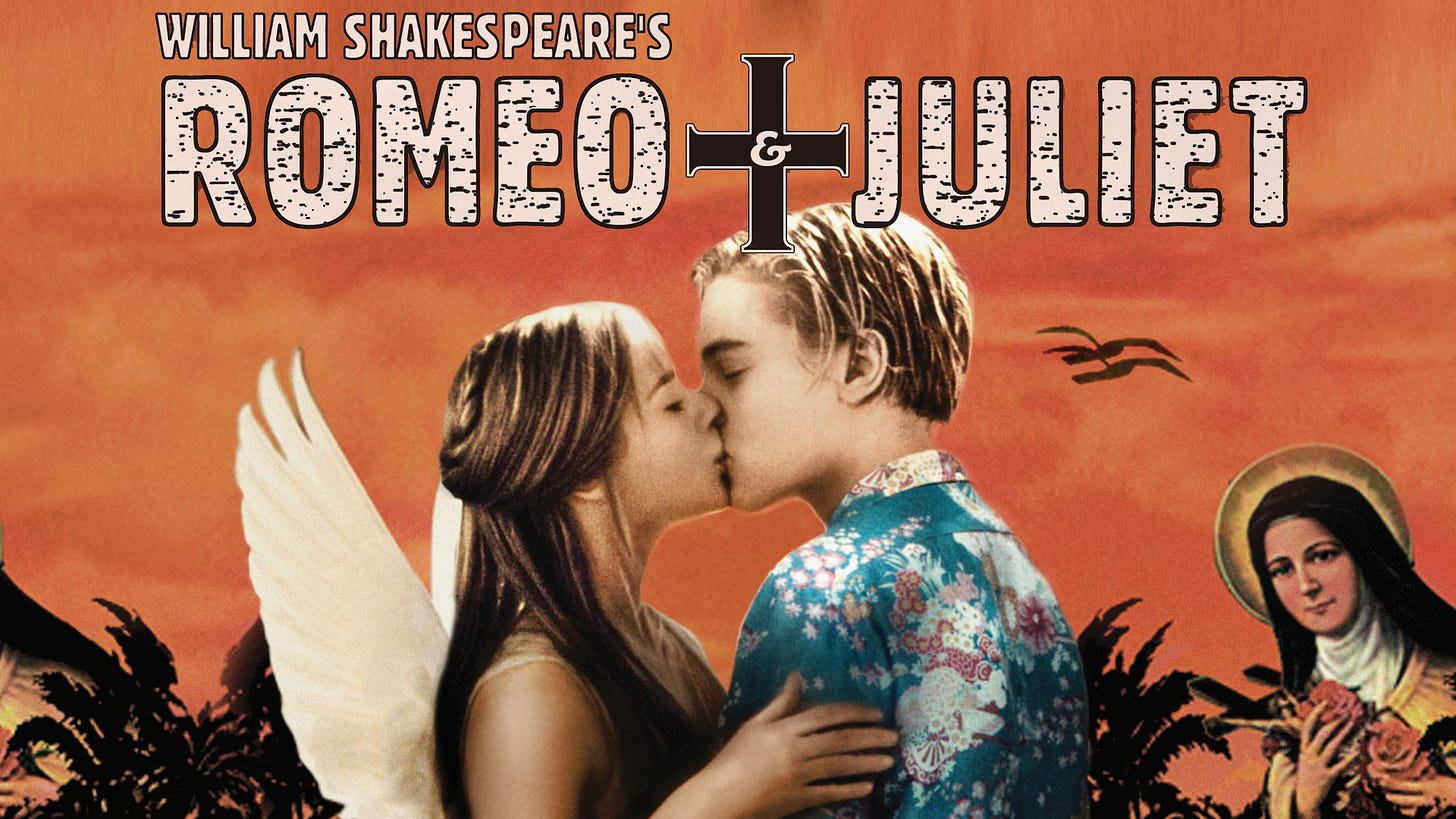

William Shakespeare’s Romeo + Juliet is an adaptation of the playwright’s most famous romance, directed by Australian filmmaker Baz Luhrmann and starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Clare Danes as the titular star-crossed lovers. This is an exciting edition of the column for me to write, because it means we’re finally meeting one of my favorite actors of all time.

The young male lead of Romeo + Juliet continues to be one of the most prominent faces in all of movies today, as his beard grows long and his roles grow ever more complex. But we’re not dealing with just one fascinating cinematic figure today. Let’s talk Baz.

I’ll be honest and maybe harm any intellectual credibility I’ve ever had: I’m not someone who immediately gets Shakespeare whenever I see one of his plays live. I need the guiding hand of an initial plot summary and a cool 10-15 minutes of exposure therapy to the language in order to get into the groove of the storytelling. And even then, the language used is so simultaneously archaic and layered that parsing it requires the same mental effort as when I try to translate spoken Spanish on the fly. I generally get what Shakespeare plots are about, but often the dialogue just overwhelms my mind.

Baz Luhrmann movies have the same effect on me.

Luhrmann’s visual style is chaotic in a way that you don’t often see in major studio releases. The zooms are fast, the pans are closer to spins, and his use of montage makes you feel like you’re watching a trailer for the movie instead of the final release. His frantic editing cuts aren’t the result of shoddy craftsmanship, but rather an intentional cinematic language that uses a quickened pace to convey heightened emotions. This isn’t a unique strategy; plenty of directors have attempted to visually unmoor the audience in an effort to emphasize the emotional turmoil of a situation. The difference here is that Luhrmann’s movies live in that unmooring.

This always leads to batshit openings for Luhrmann’s movies, as the director frequently makes use of flashforward, in media res, and foreshadowing as soon as his movies start. I’ve found that this style means that when I watch one of this guy’s movies, it takes me a few scenes before I’ve grasped what’s happening visually, after which I’m acclimated enough to the filmmaking that I can let the images and editing wash over me.

Sound familiar?

Luhrmann’s style and filmography scream passion. If you can believe it, this is a result of the man being a lifelong theater kid.1 Born in Australia in the ‘60s, Luhrmann attended the National Institute of Dramatic Arts in Sydney as a young man, with a focus on the local theater and opera scenes. Inspired by his mother’s work as a dance instructor, the young Aussie created Strictly Ballroom, a stage musical comedy set in the world of competitive ballroom dancing that strangely features a potent anti-fascist narrative.

This slant made the show a massive hit when it premiered at the Czechoslovakian World Youth Drama Festival in 1986. Allegedly, this first ever showing of Strictly Ballroom received a 30 minute standing ovation due to the audience’s connection to the struggle against groupthink and overbearing bureaucracy depicted in the show. Luhrmann had created a story about competitive ballroom dancing that was crossing boundaries and deep ideological barriers during the waning years of the Cold War.

After years of running successfully in Sydney and struggling to find funding for the adaptation, Luhrmann was finally able to turn Strictly Ballroom into a feature film in 1992. Almost immediately, the movie was a smash hit in his native Australia, breaking box office records, sending pieces of the soundtrack to the top of the charts, and staying in some theaters for over a year. The movie won basically every movie award that exists down under, and had equally rapturous showings at international film festivals like Cannes. Indie distributor Miramax picked up the distribution rights, and though it barely made a blip in America, Luhrmann’s movie did so strongly everywhere else that it didn’t really need to.

I was unaware of Strictly Ballroom or its importance in Baz Luhrmann’s career before starting my research for this column. This debut feature marks the start of the director’s unofficial Red Curtain Trilogy, a term for his first three movies. Each examines an aspect of theater as a running motif, hence the name. Strictly Ballroom explores dance, and though it isn’t a musical in the sense that the characters don’t sing any songs, it has some incredible choreography, some of the best I’ve ever seen on screen.

The story goes basically where you think it’ll go, but again I like how boldly it pushes back against conservative, autocratic mindsets where powerful individuals establish the standards and practices for an entire group. Strictly Ballroom is a supremely fun time, and if you’re in the mood for a musical or something like one, I recommend it [4/5].

Though his first movie didn’t make much of an impression in America (I’m unclear if it existed in theaters here beyond a couple of weeks in New York and LA), Luhrmann was still highly sought out by Hollywood. Once 20th Century Fox signed him on to make a movie, Luhrmann expected to be a cog in the machine, making whatever corporate slop was needed by the executives calling the shots.

Instead, the director was given a shocking amount of creative freedom for someone who had never made a major Hollywood hit. He was allowed to use all his own familiar crew behind the scenes (all Aussies), and given the opportunity to pitch an original idea.

Luhrmann returned to his theater roots for inspiration. His mind wandered to Shakespeare, perhaps because of the saturation of adaptations. Though peers like Branagh were using the Bard’s work to create prestige pictures that found themselves perhaps a bit self-important, Luhrmann remembered something that seemingly no one else wanted to admit: Shakespeare’s main goal as both writer and theater operator was a packed house every night. His works were crowd pleasers, written as a way to draw both Elizabethan drunks and aristocrats into the Globe Theater performance after performance.

If that Shakespeare, the one who wanted to draw the biggest crowd possible, was to direct one of his plays in 1996, what would it look like? Would it be stifling and dripping with a high estimation of its own importance? Or would it make use of the evolving styles to get as many people as possible to see it?

Luhrmann decided to take Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare’s defining doomed romance, and adapt it visually for the ‘90s while directly porting the dialogue from the original play. It was a strange prospect, but the director had confidence in his vision. He still needed to sell it to 20th Century Fox, however, which he knew could be a long shot. Thankfully, the director had a generational star ready to help.

The origins of Leonardo DiCaprio’s involvement with Romeo + Juliet shift slightly depending on which year Luhrmann is telling the story in. In 1996, just after the movie’s release, Luhrmann bragged about seeking out the young star to get him involved as soon as possible. Decades later however, he admits to not knowing who DiCaprio even was at the time, with the actor needing to audition to even get the part despite one Oscar nomination already under his belt.

I can see why Luhrmann would want a bit more credit 30 years ago. Imagine being the guy who gave Leonardo DiCaprio his big commercial break.

Sure, the 22-year-old DiCaprio had been acting on television since he was 5, with recurring roles in shows like Growing Pains and roles in small-budget movies like Critters 3. And yes, the young actor had wowed critics everywhere with his performance in What’s Eating Gilbert Grape in 1993, only losing the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor to Tommy Lee Jones for his role in The Fugitive [4/5]. But what DiCaprio had never been involved with was a commercial hit, a big swing for a broad audience with the marketing budget to make it happen.

It sounds absurd now, when the man’s filmography speaks to his status as one of the greatest and most popular movie actors of all time, but we’re meeting a version of Leonardo DiCaprio who’s something of an unproven upstart, at least when it comes to the box office.

However DiCaprio first caught wind of Luhrmann’s new project, the actor knew he wanted to be involved. In an effort to convince the director that he’d be perfect for the lead, Leo and a posse of friends flew down to Australia (on their own dime) to shoot a test scene with Luhrmann. The director has never revealed who performed the duel between Romeo and Tybalt with DiCaprio, but the final result was enough to convince 20th Century Fox, despite the antiquated language.

“Oh,” the executives said, according to Luhrmann. “They’re gangs. Sure, that could work.”

With a $15 million budget secured, pre-production began in Canada and Australia ahead of a shoot in Mexico. Teen actress Claire Danes, most notable at this point for her part in the 1994 version of Little Women, was cast as Juliet across from DiCaprio, and the rest of the troupe was filled with talented character actors (including To Wong Foo highlight John Leguizamo as Tybalt!).

The goal was to bring the conflict of the Montagues and Capulets to the ‘90s, meaning these couldn’t just be rival families anymore. They had to be gangs, each at the throat of the other and only loosely maintaining a respectable, legal front in the corrupt city of Verona. Luhrmann was inspired by Miami and Mexico City in designing this setting, but ultimately chose to depict it as its own unique, fictional destination.

The crew made copious use of sets to ensure that they could control every aspect of this fake city like a stage show. This meant, for example, populating a stretch of desert with palm trees and a fake boardwalk to create a chill beach for Romeo and his allies to hang. Some exteriors were shot in Mexico City, but others, such as the iconic Capulet pool, were interior sets built to look like they were outdoors. All the better to capture the madness, I suppose.

Luhrmann was working with a wild idea and a relatively small budget. He knew that if this project failed, the suits would be happy to have him making junk for the rest of his career. At the same time, he was a young creative who wanted to develop and showcase his own evolving style. If he played this safe, he’d be letting himself and Shakespeare down.

As someone who was freshly one-year-old when this movie finally released, I’m think this final product is something that both director and Bard should be happy to hang their hats on. Not that that feeling came right away. The first time I watched Romeo + Juliet last year, I thought it was just alright. On this most recent rewatch, I realized that it’s one of the best movies of 1996.

I will add a caveat immediately: this movie marks the birth of the “Baz Luhrmann Cinematic Style,” and it is not for everyone. If you enjoy static cameras, restraint, or any form of minimalism, Luhrmann is not your guy. Some of the best filmmakers make you forget that you’re even looking at a screen as you watch their movie. Baz will make you more aware of that screen than any other director. The effect of his constant showmanship is frequently bombastic and occasionally nauseating. I’ve seen a lot of this guy’s movies and have learned to love his style, but I also have heard plenty of viscerally negative takes on his cinematic palette.

Here’s a test to see how much of Luhrmann you can stand: watch the first scene of Romeo + Juliet. I’ve linked it here below. See how far you can make it through without saying “That’s enough of that.”

Personally, I think that this scene is awesome. It sells the chaos of the gang war between the Montagues and the Capulets, but also clearly shows how much of this rivalry is stupid bravado for the sake of nothing but ego. Tybalt is simultaneously the coolest and lamest man to ever exist. Every person involved in that opening shootout acts like a moron because that’s what they are. These supposedly noble protectors of family honor get into a gunfight at a gas station.

The movie looks and sounds stupid in this scene because that’s what we’re supposed to be feeling about this whole conflict. We’re not getting a dramatic, overwrought moment to kick off the movie because Luhrmann wants us pointing and laughing at the futility driving the core rivalry of the plot. All the better to slow things down once we meet our titular lovers.

Romeo + Juliet doesn’t work if either of those two lovebirds fails to convey the terrible tragedy and aching passion of their intense teenage romance. DiCaprio and Danes feel tailor made for the task. Teenage girls in the ‘90s were no match for the boyish good looks and dark eyes of young DiCaprio, so it makes sense that Juliet would fall for his version of Romeo. Similarly, Danes is adorable in the film, bringing a charming beauty to the young Capulet. Their wordless moment of meeting through a fish tank at a Capulet party is both deeply romantic and a cinematic foreshadowing of their ultimate inability to be with one another; Luhrmann pans the camera in a way to reveal the lover’s proximity through the glass to be nothing more than optical illusion.

Scenes like this and the later mutual confession of love in Juliet’s backyard pool reveal Luhrmann’s skilled hand at using the visual language of film to convey emotion. These passionate moments between Romeo and Juliet are slow, shot methodically and with a gorgeous sense of lighting so that the audience can bask in the sheer romance of what’s on screen. The sped up footage of Juliet’s mother getting dressed in her gaudy Cleopatra outfit or that incredibly ludicrous gas station shootout set the stage for scenes where the rest of the movie is stripped away and all we get is our title characters.

It’s easy and frankly correct to point out that the central romance of Shakespeare’s story is the overly melodramatic emotions of two teenagers left too much to their own devices. I think that’s the point. The hateful obsession between the other Montagues and Capulets is just the other side of the same passionate coin that draws Romeo and Juliet together. Are we more willing to accept a generation-spanning family rivalry as a normal thing to happen over misguided love between two hormonal teens? One of those things happens a lot more than the other in real life.

Luhrmann’s choice to contrast the original Elizabethan dialogue of Shakespeare’s play with a modern setting, sense of style, and soundtrack won’t play well with any purists out there. But if the director was trying to lure people into the theater in the spirit of the original Bard, this strange idiosyncrasy was a great way to do it. The result is eye catching, intriguing, and undoubtedly authentic to the source material. There are some changes made to the text of the play to squeeze the runtime down to a svelte two hours, but if you were to close your eyes and just listen to the words being delivered by the actors, you might think that this was a straightforward vision of Romeo & Juliet. Well, that is until you get to one of a few legendary needledrops: Radiohead, The Cardigans, a boy’s choir rendition of Prince, all can be found scoring some of the film’s most important moments.

Luhrmann and his team had a blast redefining the world to match the dialogue. There are no swords in Romeo + Juliet, despite their many references in the dialogue. Instead, everyone bears firearms and simply refers to them as blades. Some soliloquies become internal monologues, the Prince of Verona becomes the Chief of Police, and the Capulets become a clan of devoutly Catholics Latino gangsters. This last one isn’t for any practical storytelling purpose, but it does allow for some incredible imagery. If Shakespeare was the bombastic showman that Luhrmann thinks he was, then he would have adored the thousands of candles and bright neon crosses used to convey the Capulets’ gaudy piety.

The cast around DiCaprio and Danes gives it their all. Pete Postlethwaite is the coolest priest in fiction as Father Laurence, and Harold Perrineau absolutely steals the show as Romeo’s best friend Mercutio, now depicted as a cross-dressing badass with the best ecstasy in Verona. John Leguizamo and Paul Rudd don’t have a ton of screen time as Tybalt and Paris respectively, but they’re both memorable as elements of Juliet’s story. I don’t have any complaints with any of the performances here. Every actor is fully onboard with Luhrmann’s vision of Romeo + Juliet as frantic gang warfare interspersed with tender romance. It’s like West Side Story, but with less subtlety.

Romeo + Juliet isn’t for everyone. It’s style is strange and the contrast between the language and the visuals is jarring to say the least. When I first watched it last year with my wife and some friends, I thought it was just okay. My biggest takeaway at the time was the revelation that it was the film referenced in “Exit Music (For a Film),” a Radiohead song I’ve listened to and enjoyed for years.

Something clicked this time around for me though. Maybe it was the weak run of movies ahead of it in this column, but Romeo + Juliet stands tall as a highlight of 1996, something that deserved more success than it got. And it got a lot of success.

Luhrmann says he wasn’t explicitly instructed to make a movie that would appeal to the MTV crowd. The fast-paced editing and dramatic romance of Romeo + Juliet look and sound like a music video because he thought it’s what Shakespeare would have wanted. What was intentional was a marketing campaign that leaned hard toward the younger demographic.

Frequent ads on MTV and during shows with young audiences like Friends and The X-Files targeted a young crowd who may see themselves in the title characters, or at least be drawn to DiCaprio as a not-quite-teen idol. Bob Harper, president of marketing at the time at Fox Film, had this to say about the film’s marketing:

We wanted to make a movie that was tremendously relatable to young people. It was a very targeted campaign. We said: 'This is what it is. Either you get it or you don't.”

The kids got it. The movie debuted at number one, driven primarily through a largely teenage audience. All the coverage I found from the time is from stunned writers reporting how everyone else was also stunned by Luhrmann’s success.

Bernie Weinraub from the New York Times wrote about being shocked that teens of the ‘90s would even be interested in the themes of Romeo + Juliet, which is just insane. As Luhrmann said in an interview from the time, Shakespeare dealt in primary mythologies. Teenagers are still as hormonal and impulsive in the ‘90s as they were in Elizabethan times; why wouldn’t they be interested in beautiful peers falling in love in a cool looking movie?

To be fair to the stuffy old critics who reviewed the movie, the general consensus from them was positive. A 74% on Rotten Tomatoes is surprisingly high for a movie that proved controversial amongst purists for its use of the original language. Roger Ebert didn’t care for it, calling it a “mess” and its swings at relevancy “greatly depressing.” I like Bob McCabe’s 4/5 review for Empire Magazine though:

Shakespeare's name fills up the title, but this is clearly Luhrmann's vision and it's a genuinely inventive one. Yes, at the end of the day you can say that it's just a gimmick designed to sell the Bard to the masses. But a bloody good gimmick all the same.

The kids of America shocked the world by buying enough tickets to help push Romeo + Juliet above presumed box office king Sleepers. An $11 million gross isn’t the biggest weekend take of 1996, but it nearly recouped the film’s production budget in one fell swoop, and was enough to propel Luhrmann’s vision to the top. The movie stayed in the Top 10 of the charts until mid December and lingered in the cineplexes until, fittingly, the next Valentines Day. A final domestic gross of $46 million would already prove Romeo + Juliet to be a success, but a remarkable $100 million from the international box office turned it into a smash.

The New York Times reached out to Kenneth Branagh about this success, and the guy couldn’t have been happier. The actor/director just loves Shakespeare and his lingering posthumous success, but it wasn’t just ideological joy. Surely, this movie’s success boded well for his upcoming Hamlet adaptation that was releasing that Christmas. Except it didn’t.

That Hamlet adaptation, despite a star studded cast, barely released into any theaters and only made $4.7 million on an $18 million budget, a much smaller gross than Romeo + Juliet with a slightly bigger budget. Today, hardly anyone remembers it even exists. I won’t be so bold as to say that Luhrmann’s style of Shakespeare adaptation killed Branagh’s, but it did make any new version of the Bard’s work that didn’t appeal to a larger audience seem outdated. I don’t think a movie like 10 Things I Hate About You, 1999’s modern take on The Taming of the Shrew, happens without Romeo + Juliet.

In interviews from the time, Luhrmann says that he suspects that 20th Century Fox expected the movie to fail so that they could justify putting him to work on garbage like Jingle All the Way [his words, not mine, but that movie does suck. 1.5/5]. The success of Romeo + Juliet doesn’t seem obvious in hindsight, but I would have respected it as a big creative swing, even if it had missed. Instead, the director made a splash in Hollywood with a visual feast that no one else could have directed, and firmly established Leonardo DiCaprio as a leading man.

All these years later, the boldness and creativity of Romeo + Juliet still pops off the screen, as does its obvious reverence for its source material. Luhrmann not only used the dialogue straight from the original play, he conveyed its themes with a visual style that made everyone take notice and get a ticket to see what the hype was about.

Shakespeare would have been so proud.

Rating: 4.5/5

Next Week: If a movie does extraordinary business at the box office, you expect that it will stick around in cultural memory more than not at all. I’ll be more than happy to disprove that notion next Friday as we review Ransom, one of the highest grossing movies of 1996.

See you then!

-Will

The term “theater kid” is age neutral. Baz Luhrmann is 62 years old but you know this Aussie is still a theater kid

If only i could gift you the experience of watching John Leguizamo manifest Tybalt Capulet on the projector screen of our 8th grade English Classroom...