A Life Through Film #008: Waiting to Exhale

This dispatch from the Golden Age of Black Cinema is for the ladies

Release Date: 12/15/1995

First Weekend At Number One: 12/15/1995

Weeks at Number One: 1

Thanks for reading! This is my ongoing series where I track the evolution of American culture in my life by reviewing every number one film at the weekend box office since I was born in chronological order. If you haven’t already, I highly recommend reading my introduction post here.

It seems that once a decade, Hollywood learns an extremely valuable lesson it had forgotten about representation.

In a 2019 piece for PBS, Rawan Elbaba talked to a diverse group of over 140 middle and high schoolers about the value of seeing characters that share their race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, or ability in movies and TV shows. The consensus was clear: so long as the depictions don’t slip into harmful stereotypes, these students found it important to see themselves represented in entertainment media. Some pointed to benefits to their self-esteem, others found it important as part of their developing identities.

One high school junior had an interesting thought on the motives behind such representation, however:

Diversity equals money in today’s world, which is cool, I guess…[but] it’s cooler to have pure motives.

As much as I agree and wish that diverse movies could be made just for the sake of representation, their potential for making money is a far bigger motivator for studios. This was especially the case when the article was published in 2019.

Movies with diverse casts or from non-white countries were having a strong moment at the box office when Elbaba spoke to those teenagers. Black Panther [4/5] and Crazy Rich Asians [3/5] were massive hits that crossed over to American audiences of all stripes. More thoughtful independent fare like Sorry to Bother You [3.5/5] and Moonlight [4/5] and animated films like Spider-Man: Into the Spider-verse [5/5] also found success with casts that omitted the Hollywood default of white, male leads. Within a few months of Elbaba’s article, Bong Joon-Ho’s Parasite [5/5] would become a massive international hit, eventually becoming the first non-English speaking film to win Best Picture at the Oscars.

Though this era’s rise in Hollywood diversity represented multiple groups and identities, it’s tough not to see it as the capper for a stellar decade of films made by and starring Black creatives. The 2010s saw the rise of new movie stars like Michael B. Jordan, Daniel Kaluuya, Lupita Nyong’o, and the late Chadwick Boseman. It gave us new auteur directors whose film releases are both cultural events and explorations of aspects of the African-American experience, such as Jordan Peele, Steve McQueen, and Barry Jenkins.

I could go on. There was truly a cavalcade of great Black films from the 2010s. Candice Frederick put it best when, writing for Essence, she declared that “the 2010s will go down as one of the most exceptional eras in Black movie history.”

Time, as it’s been said, is a flat circle.

It is the mid 1990s, and many studios are trying to play catch up. The critical and commercial success of movies like Do the Right Thing [3.5/5] and Boyz n the Hood earlier in the decade had caught many of them off guard. Not only were these movies by and starring Black artists doing well financially, they were breaking the expectations of what movies like that could accomplish. Sure, Blaxploitation films of the 70s had made some money, but those had never crossed over to a “wide” (white) audience.

Now, the studios were realizing they could market relatively low-budget, high quality Black films to white audiences to great success. Directors like Spike Lee and John Singleton were suddenly in high demand, and studios began calling up independent filmmakers like Wendell Harris Jr. and Keenan Ivory Wayans, hoping to break the next great Black director.

“In Hollywood,” James Greenberg reported for the New York Times, “Black is in.”

By the end of the 1990s, the decade would, like the 2010s, be known for the success of Black films at the box office and the creation of new African-American stars like Wesley Snipes, Cuba Gooding Jr., Denzel Washington and Laurence Fishburne. Some have even referred to the ‘90s as the Golden Age of Black Cinema.

But was this always the most positive representation? Some of the most acclaimed, culturally significant films of the early 90s were bleak examinations of young Black men in dangerous neighborhoods. True, these stories and settings were fresh in the zeitgeist thanks to the popular rise of gangster rap at around the same time. But the new Hollywood “trend” ran the risk of going back to the same reductive well over and over again, thereby reinforcing negative stereotypes to general audiences.

20th Century Fox probably didn’t have “pure motives” when they greenlit a movie that stood apart from the rest of Black cinema of the 90s. But if their goal was to make money, they certainly accomplished that with Waiting to Exhale.

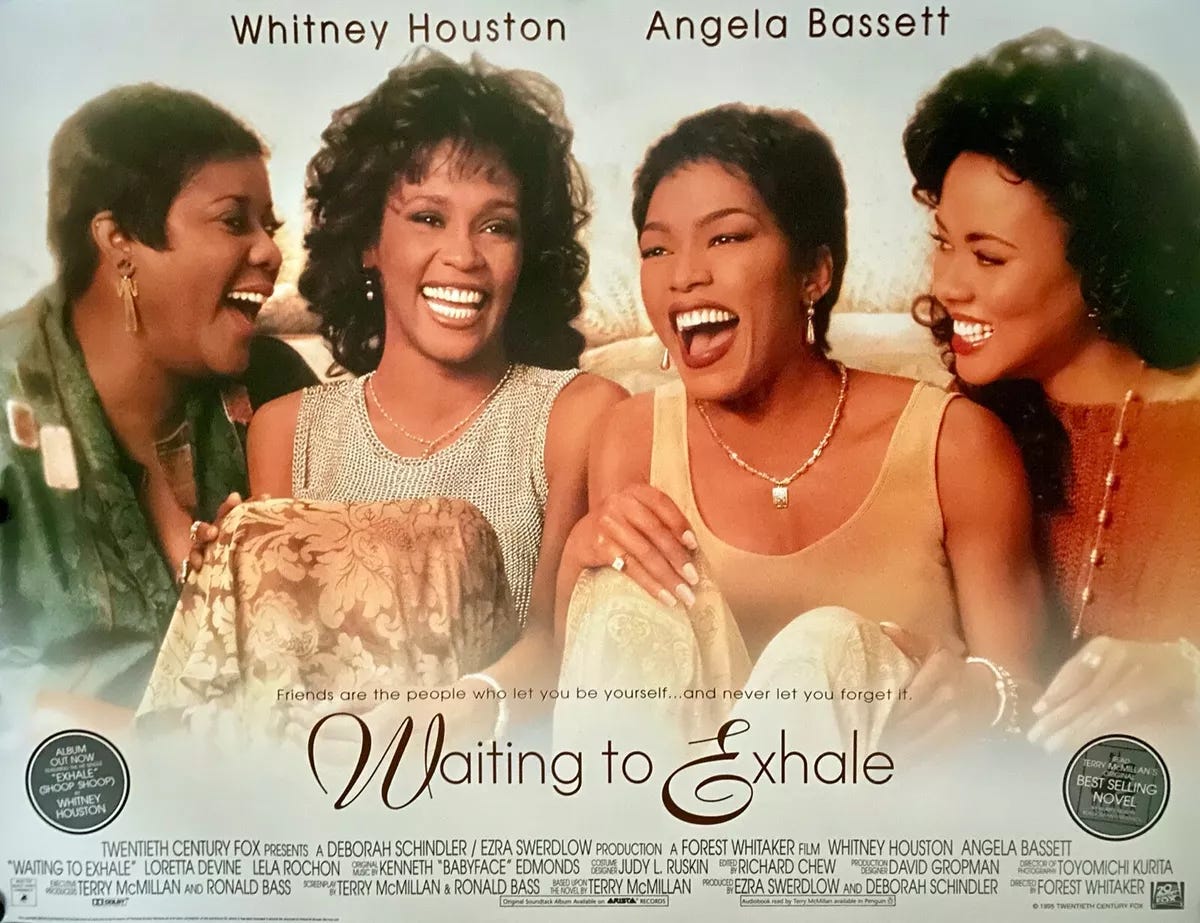

Directed by Forest Whitaker and starring Whitney Houston, Angela Bassett, Loretta Devine, and Lela Rochon, Waiting to Exhale follows four Black friends in Phoenix over the course of a year as they deal with various relationship issues, relying on their bond to push through them and find personal happiness.

The film is an adaptation of Terry McMillan’s book of the same name, which was released in 1992 and almost immediately became a smash success. The New York Times Best Seller had sold 3 million units by 1995, with a massive audience of women of all races reading the novel. Combined with the push for more movies centered on Black stories, McMillan’s book was as no-brainer a choice for adaptation as one could ever hope to be.

After buying the book’s film rights, 20th Century Fox got McMillan onboard early, making her a key part of the creative development of the movie. In addition to having McMillan write the screenplay (which she did with the help of Ron Bass, a pretty accomplished screenwriter to this point with credits like Rain Man and Sleeping With the Enemy), the studio wanted her to pick the director for Waiting to Exhale. Her choice? Forest Whitaker.

Yes, that Forest Whitaker. I had no idea about this before this column, but the Academy Award winning actor also has a handful of directorial credits to his name as well. In 1993, he directed Strapped, his first film, for HBO (though it’s no longer on MAX, you can watch the whole thing on YouTube here). Strapped follows in the trend of gritty urban dramas of the time, focusing on a young man from the streets of Brooklyn who tries to go straight but ends up embroiled in his neighborhood gun trade.

The movie has such good intentions, attempting to show both the dangers of illegal guns on the street as well as the social circumstances that would lead a regular person to get involved with their black market. But the movie waffles between baffling directorial choices and boring, overly long dialogue scenes with high frequency. Despite a cool soundtrack of early ‘90s hip hop, I can’t recommend the movie, even if you’re a total nut for urban crime dramas [Strapped is a 1.5/5].

Contrary to my views on it, critics dug Strapped, earning Whitaker some positive attention as a director. He had already proven himself as a talented actor, thanks to memorable roles in films like Oliver Stone’s Platoon [4/5], but now he had some momentum for his work behind the camera. McMillan must have really enjoyed Strapped, because she brought Whitaker in front of a boardroom full of producers and offered him the job. Whitaker, inspired by the prospect of centering a film around four successful Black women, accepted.

While McMillan didn’t have any actresses in mind for the adaptation, the new director did. It was Whitaker’s idea to bring in the two big stars, and they’re maybe the two biggest names he could have pushed for to join Waiting to Exhale.

By 1995, Angela Bassett was a bonafide movie star. She had earned some attention with roles in movies like Boyz n the Hood and Malcolm X in the earlier part of the decade. But after her Oscar-nominated performance as Tina Turner in the ‘93 biopic What’s Love Got to Do With It [3/5], the actress was extremely in-demand. Waiting to Exhale was actually the fourth movie Bassett was in that was released in 1995 (the other three being Panther, Vampire in Brooklyn, and Strange Days). Whitaker asking Bassett to join the cast of Exhale makes sense, all things considered. She was a talented, hard working actress who had a track record of hits.

His reaching out to Whitney Houston was a more inspired decision. The pop star was still a big deal by this time, but had become known more as a lightning rod for the tabloids thanks to her tumultuous relationship with singer Bobby Brown. Plus, Houston had only acted once before this, in 1992’s The Bodyguard with Kevin Costner. That movie had done well, but critics did not love it or Houston’s performance in it. Nowadays, it’s mostly considered a piece of trivia when talking about her iconic version of “I Will Always Love You.”

Houston was still a beloved pop culture figure at this point, and her role in Exhale would bring even more eyes to the final product. And she was excited for the role as well. In an interview with VH1 at the time of the movie’s release, the pop diva explained that she took the role because the script was filled with women and stories she felt like she already knew from her personal life.1

With Houston and Bassett onboard, Whitaker rounded out the primary foursome for Exhale with longtime Broadway actor Loretta Devine and relative newcomer Lela Rochon. The troupe found their way to the American Southwest and began work on McMillan’s adaptation.

In every piece of press I watched for this movie, the central cast talked repeatedly about how fun the filming experience was and how they all bonded as real friends. That’s reflected on-screen. Houston, Bassett, Rochon, and Devine share some fun, believable chemistry as a friend group in Waiting to Exhale. Some of the better scenes in the movie are the times some combination of the four get to just hang out and gab.

The problem is that the movie’s structure doesn’t allow for enough of those moments. 45 minutes of Waiting to Exhale goes by before we get a scene where our four primary characters share the screen. I know it can be tough to schedule hangouts with friends as an adult, but this group friendship is supposed to be the point of the movie! Between the weird pacing and poor definition of the dynamics of the group (how long have they known each other? Who’s closer to who? Did Houston’s character know all of them before moving into town at the start of the movie?), the collective friendship at the heart of the movie is repeatedly undermined despite the charming moments it gets.

This is all just a symptom of Waiting to Exhale’s overall uneven structure. Each of the four women has an arc, but these stories are not created equal. Played by Rochon, Robin’s arc of learning self-respect instead of just hopping from guy to guy ends nicely, but lacks any stakes before then. Savannah, Houston’s character, straight up does not have a story to sink her teeth into until the last 40 minutes of the movie, when she realizes that she has value as a successful single woman and doesn’t need to put up with a man who will never end up leaving his wife for her.

The two most compelling arcs belong to Devine and Bassett, both centered on rediscovery of self. Devine’s Gloria finds herself losing both her son (hey, it’s Donald Faison!) as he grows into a young man who wants to travel the world and the boy’s father (hey, it’s Giancarlo Esposito!) as he comes out as gay and leaves them. Gloria finding that she still has value and is worth loving is actually really sweet, helped by good chemistry between Devine and her eventual love interest, Gregory Hines.

The arc of Bernadine, played by Angela Bassett, is by far the best part of Waiting to Exhale. Blindsided by her wealthy husband leaving her for a white woman, the housewife must simultaneously fight for herself in divorce court while also rediscovering the woman she was before dedicating over a decade of her life to her husband and children. Bassett is an incredible actress who gets so much to sink her teeth into during the movie, both by herself and in scenes with the other leads. She is handedly responsible for the two absolute best moments in the movie.

If you know any image from Waiting to Exhale, it’s likely Angela Bassett looking fine as hell while she sets a car on fire and smokes a cigarette. The whole scene leading up to that set piece is, thanks to her performance, just killer. For what feels like the first time in her life, Bernadine exhibits true rage at what she has lost and the person she had become by putting her husband first during their entire marriage. Bassett fully lets loose a torrent of anger, grief, disappointment, and disgust, finally reaching catharsis by lighting both a cigarette and luxury vehicle with the same match. Incredible.

That scene happens less than 20 minutes into the movie, and nothing that comes after approaches its level of quality. But later in the movie, Bassett comes close to it thanks to an unexpected dance partner. As she sits at a high end bar, still stewing in anger over her divorce, Bernadine is joined by a handsome D.C. lawyer, played by Wesley Snipes (making his second appearance in this column). After some flirting to open her up emotionally, Snipes admits to being married to a woman dying of breast cancer. As he talks about the love he still holds for her despite her terminal diagnosis, Snipes hits grief, relief , joy, melancholy, and every emotion in between. Bernadine realizes that a loving marriage can exist, despite her experiences, and is flush with hope. The two begin an emotional affair.

(Forgive the video quality, the only footage of this scene on YouTube is from a literal camcorder pointed at a CRT)

These two scenes are the best moments of the best story in Waiting to Exhale. Unfortunately, the rest of the movie doesn’t even come close to matching their quality. Like I said earlier, the big problem with Exhale is the pacing. Whitaker tries to cut between the characters’ arcs from scene to scene, but does so unevenly. There are multiple 15 to 20 minute chunks of this movie without one or two of the protagonists getting any storyline progression shown at all. But then we cut back to those characters and it feels like we’ve missed important story beats! The movie is least watchable when it does this to Bernadine’s story, especially when it’s in order to show the much less interesting Robin storyline.

It’s also disappointing for the movie to be so about these women and their relationships with men. They all have interesting professional and familial lives hinted at throughout the movie, but none of that is ever the focus. As a result it never feels like we get the full portrait of any character, just what that character is like relative to the men in her life.

The performances, like the pace, are uneven. Bassett is killer throughout, and Devine is very good as well. Like I said though, Houston doesn’t really have anything to work with until the end of the movie, and even then she’s not an incredible acting talent. Rochon has a few good moments, but she comes off as too flat for such a flamboyant character much of the time. The supporting cast is also so-so, though I’ll give props to Hines and Snipes for the best male performances in this chick flick.

I thought Whitaker’s directing in Strapped had an amateurish feel to it that was occasionally charming but mostly confusing. Here, he’s competent behind the camera but not anything special. A couple of his special touches do return from his debut; the rapid camera zooms to emphasize character focus is a fun touch when used sparingly, but the dramatic slo-mo at the very end is wholly unnecessary and honestly a little nauseating.

One very smart move that Whitaker made as director was commissioning the movie’s star-studded soundtrack. He asked Houston to collab with hitmaking writer/producer Babyface to put together a companion album for Exhale full of songs inspired by and part of the final movie. The musical pair ended up making an hour-long collection of mostly original tracks featuring an all-female list of past legends and contemporaneous stars. Houston herself, initially hesitant to fuse an acting job with a singing one again after The Bodyguard, ended up singing three songs for the soundtrack, including the title track.

“Exhale (Shoop Shoop)” ended up being a big hit, and was the last Whitney Houston song to ever top the Billboard Hot 100. The album it came from was an even bigger hit, eventually going seven times platinum and spinning off a number of other Top 10 hits from artists like Mary J. Blige and Brandy.

I’m so-so on the Waiting to Exhale soundtrack. While there are certainly some highlights (that title track, the Brandy song, and Chaka Kahn’s rendition of jazz standard “My Funny Valentine”), I find a lot of the sultry R&B sound of it to be dated in a way I don’t love. I recognize there are tons of people who adore that slow, sexy sound from the ‘90s. If that’s you, I think you should listen to the Exhale soundtrack immediately, since it’s over an hour of that. If we’re talking my personal favorite albums of 1995 though, I don’t think it’s touching What’s the Story (Morning Glory) or Brown Sugar.

I also can recognize that Waiting to Exhale the movie is not fully to my specific tastes, but I am also not the target audience for it. It comes back to representation. As a straight white guy, I’ve never had to struggle to find myself in movies or TV at any point in my life. Something like Waiting to Exhale, a Hollywood studio film about four successful Black women, doesn’t come around very often though. There is value in that for the represented group, and if that makes this movie a sentimental favorite for women of color, I think that’s fantastic.

At the time, there was some pushback by some that the movie was anti-man, since most of the love interests for the principal cast were routinely rotten dudes. On the one hand, I don’t think this is the case at all. The four women at the heart of the movie are not meant to represent all women everywhere, so why should the men represent all men everywhere? And on the other hand, it strikes me as really insecure that any guy would look at a romantic comedy so centered on women like Waiting to Exhale and cry out “BUT WHAT ABOUT THE MEN THOUGH,” especially when women were expected to put up some truly heinous female representation in ‘90s action movies.

The critics were mixed on Waiting to Exhale but generally positive overall. Roger Ebert gave it 3 stars out of 4, which I’m mentioning mostly because I think the image of Roger Ebert sitting in a packed theater enjoying this movie is very funny. Kenneth Turan of the LA Times called it “easy listening for the eyes if you’re in the mood and aren’t too demanding,” while Edward Guthmann of SF Gate shared my serious issues with the movie’s pacing in a negative review.

Though critics were mixed, the mass appeal of the movie was clearly there, because Waiting to Exhale ended up doing great numbers at the box office. Though only at the top for one weekend, the movie did solid business for months after its December release. It’s final gross: $81 million on a $16 million budget. Another studio’s bet on Black film had paid off handsomely for them.

The success of Waiting to Exhale that first weekend is, I think, due to three reasons. First, the movie premiered the weekend just before Christmas, during a time when much of its adult audience were off from work. It’s also a movie about friendship, making it easy to market for a season of love and goodwill. And, as Whitaker pointed out in an interview with Charlie Rose, it’s a movie that women would see in groups in order to see their dynamics reflected on screen together. He even referenced seeing crowds of women 15 to 20 deep seeing the movie together, a scale of coordination I don’t think I’d ever be able to achieve.

Waiting to Exhale was always going to have an audience, what with its successful source material and star power. But I think the uniqueness of its representation did a lot to make the movie have some staying power, both commercially and, somewhat, culturally. It’s not hard to find well-written, thoughtful writeups in praise of Exhale and what it continues to mean to many Black women. I love what the movie means to people. I just don’t love the movie itself very much. More than any other movie I’ve reviewed so far for this column though, take my opinion on this one with a grain of salt.

Waiting to Exhale: not for me, but if you really like it, I think that’s great.

Rating: 2/5

And with that, we’ve reached the end of 1995 in the column! After Waiting For Exhale’s big weekend, Toy Story moved back into the top spot during the final weekend of the year, closing it out on a strong note.

Moving forward, I’ll create a whole separate post ranking the Box Office toppers in a year once we’ve completed it in the column. But since we’ve been only been covering the last few months of ‘95 to this point, I’ll just put it right here.

This is how I would rank the 1995 movies covered in the column by my own personal taste:

Waiting To Exhale [2/5]

Next Week: We kick off our trip through 1996 with an all timer as we look back at 12 Monkeys.

See you then!

-Will

Later, after her death, Houston’s longtime bodyguard revealed that Houston had suffered her first overdose on the set of Waiting to Exhale, causing shooting to pause for a week. I had more written about this event as a sort of psychoanalysis of the late star, but reading it back it felt presumptuous and weird. Instead, I’ll just sum it up by saying I feel sorry that she still suffered from an isolating thing like addiction on what sounded like a very positive, united set